Brugada Syndrome

By: Louise R.A. Olde Nordkamp, Arthur A.M. Wilde

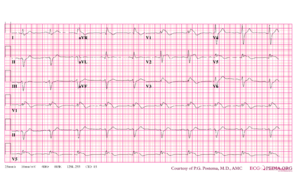

Brugada syndrome refers to a hereditary disease that is associated with a risk of sudden cardiac death. It is characterized by typical ECG abnormalities: ST segment elevation in the precordial leads (V1 - V3).[2]

The Brugada brothers were the first to describe the characteristic ECG findings and link them to sudden death. Before that, the characteristic ECG findings, were often mistaken for a right ventricle myocardial infarction and already in 1953, a publication mentions that the ECG findings were not associated with ischemia as people often expected.

General features

- The diagnosis is based on ECG findings.

- It is an inheritable cardiac arrhythmia [3] syndrome with an autosomal dominant inheritance.

- Males are often more symptomatic than females, probably by the influence of sex hormones on cardiac arrhythmias and/or ion channels.

- The arrhythmias typically occur in patients between 30-40 years of age and often during rest or while sleeping.

- The right ventricle is most affected in Brugada syndrome, and particularly (but not specifically) the right ventricular outflow tract.

- The prevalence varies between 5-50:10.000, largely depending on the geographic location (especially in some Southeast Asian countries the disease is more prevalent).

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of Brugada syndrome is confirmed in an individual with the following:

| Findings | |

|---|---|

| ECG | Type 1 ECG with coved type ST-elevation |

| And at least one of the following | |

| Clinical history | |

| - Documented ventricular fibrillation | |

| - Self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia | |

| - Syncope | |

| - A family history of sudden cardiac death <45yrs | |

| - Coved-type ECGs in family members | |

| - Inducibility of VT/VF during programmed electrical stimulation | |

| - Noctural agonal respiration | |

Physical examination

Patients can present with symptoms of arrhythmias:

- Out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest

- Syncope, pre-syncope (weakness, lightheadedness, dizziness)

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Paleness

- Sweating

Other clinical presentations of Brugada syndrome may include sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome (SUDS), which is seen in southeast Asia in which young persons die from cardiac arrest with no identifiable cause (also known as bangungut in the Philippines, lai tai in Thailand, pokkuri in Japan and dab tsog in Laos.

However, most patients with Brugada syndrome are asymptomatic and are under medical attention because of family screening for sudden cardiac death/Brugada syndrome or because a Brugada ECG was found coincidentally.

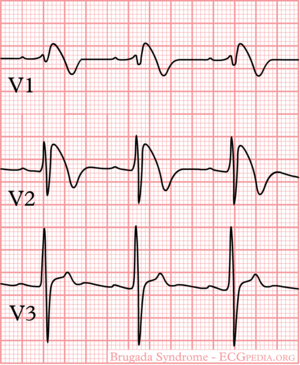

ECG tests

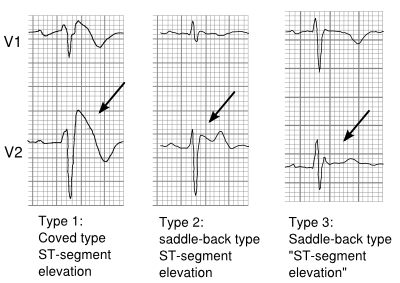

The ECG in Brugada syndrome is characterized by ST-segment elevations directly followed by a negative T-wave in the right precordial leads (V1-V3) and in leads positioned one or two intercostal space higher. It is referred to as a coved type Brugada ECG, or type 1 ECG, and cannot be explained by electrolyte disturbances, ischemia or structural heart disease. This specific ECG hallmark typically fluctuates over time, and can also be presented as a type 2 or type 3 ECG or even a normal ECG. The type 2 ST-segment elevation has a saddleback appearance with a high takeoff ST-segment elevation of ≥ 2mm, a trough displaying ≥1mm, and then either a positive or a biphasic T wave. Type 3 has either a saddleback or coved appearance with a ST-segment elevation of <1mm (figure 1). Type 2 and 3 are not diagnostic of the BrS. In some patients a type 1 ECG may only be unmasked or modulated by sodium channel blockers (such as ajmaline or flecainide) a febrile state, vagotonic agents, α-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic blockers, tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants, a combination of glucose and insulin, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, and alcohol or cocaine toxicity.

Genetic diagnosis

In only ~30% genetic variants can be detected in the SCN5A[4] gene, which results in a loss of function of the cardiac sodium channel function. This impairs the fast upstroke in phase 0 of the action potential and leads to conduction slowing in the heart. In the remaining patients sometimes cardiac calcium channel genes (CACNxxx) or potassium channel genes (KCNxx) are involved, but in most of the Brugada syndrome patients no genetic defects are found.[5]

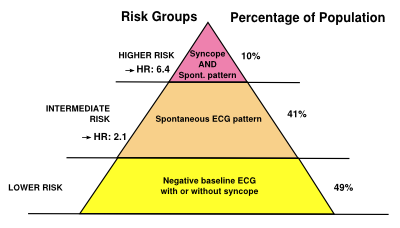

Risk Stratification

Brugada syndrome patients with symptoms (a history of VT/VF or cardiac syncope) and spontaneous coved-type ECG are at risk for future arrhythmic events. However, risk stratification[7] in asymptomatic Brugada syndrome patients is still ill-defined. Family history of sudden cardiac death, male gender and inducibility of VT/VF during programmed electrical stimulation[8] is not consistently shown to be a risk factor. Therefore, risk stratification is best done by an expert cardio-genetics cardiologist.[6]

Treatment

Lifestyle modification

- All Brugada syndrome patients should avoid drugs that could manifest a type 1 ECG and VF. These drugs are listed on www.BrugadaDrugs.org.

- Fever may also provoke type 1 ECG and VF. Patients with fever are advised to go to the hospital to make an ECG. When ECG changes are present, monitoring is warranted and antipyretics are needed.

Medication/Other therapies:

- ICD implantation is first line therapy in Brugada patients with a previous cardiac arrest, ventricular tachycardia or cardiac syncope. ICD implantation in asymptomatic patients is not advised and needs careful judgement regarding the low annual rate of arrhythmic events and high incidence rate of complications (7.5 per 100 patient-years).

- In Brugada patients with recurrent VF events or ICD shocks, isoproterenol or quinidine are known to be effective for VF suppression in both children and adults.

- Ablation of a fractionated electrogram in the epicardial right ventricular outflow tract is a promising option for VF suppression in Brugada patients in a small study, but still has to be proven in larger cohorts of Brugada patients.

References

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, LeMarec H, Nademanee K, Perez Riera AR, Shimizu W, Schulze-Bahr E, Tan H, and Wilde A. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference. Heart Rhythm. 2005 Apr;2(4):429-40. DOI:10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.005 |

- Brugada P and Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Nov 15;20(6):1391-6. DOI:10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j |

- Mizusawa Y and Wilde AA. Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Jun 1;5(3):606-16. DOI:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964577 |

- Probst V, Wilde AA, Barc J, Sacher F, Babuty D, Mabo P, Mansourati J, Le Scouarnec S, Kyndt F, Le Caignec C, Guicheney P, Gouas L, Albuisson J, Meregalli PG, Le Marec H, Tan HL, and Schott JJ. SCN5A mutations and the role of genetic background in the pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009 Dec;2(6):552-7. DOI:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.853374 |

- Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, Babuty D, Sacher F, Giustetto C, Schulze-Bahr E, Borggrefe M, Haissaguerre M, Mabo P, Le Marec H, Wolpert C, and Wilde AA. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010 Feb 9;121(5):635-43. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887026 |

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, Pappone C, Della Bella P, Giordano U, Bloise R, Giustetto C, De Nardis R, Grillo M, Ronchetti E, Faggiano G, and Nastoli J. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002 Mar 19;105(11):1342-7. DOI:10.1161/hc1102.105288 |

- Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, Gomes JA, and Mehta D. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006 Jun;17(6):577-83. DOI:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00455.x |

- Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, Della Bella P, Ottonelli AG, Sassone B, Giordano U, Pappone C, Mascioli G, Rossetti G, De Nardis R, and Colombo M. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: results of the PRELUDE (PRogrammed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Jan 3;59(1):37-45. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.064 |