Women's Heart Health

Dr. Janneke Wittekoek - Version 1

Facts & Figures

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women worldwide. According to the Global Burden of disease CVD caused almost 32% of deaths in women worldwide vs. 27% in men.1 In Europe 54% of all female deaths are from CVD vs. 43% men.2 After at least two decades of growing awareness regarding sex differences in coronary artery disease, the evolving knowledge of the clinical consequences is emerging. Although recent reports document decreases in CHD mortality for women, reductions lag behind those realized for men.3 Another worrying fact is that we see a mortality increase among younger women.4

In general cardiovascular events among women appear approximately 7-10 years later in women than in men. The lower incidence of CVD in premenopausal women compared with men of similar age and the menopause associated increase in CVD have long suggested that estrogens underlie a protective effect on the cardiovascular system for women.

It is known that estrogens improve the arterial wall response to injury and inhibit the development of atherosclerosis by promoting re-endotheliazation, inhibiting smooth muscle cell proliferation, and matrix deposition following vascular injury.5

Estrogens also decrease systemic vascular resistance, improve coronary and peripheral endothelial function and prevent coronary artery spasm in women with and without atherosclerosis. Pre-menopausal women with hormonal imbalances and estrogen deficiencies have a higher risk of developing premature atherosclerosis.6

Gender Differences in the Pathofysiology of Atherosclerosis

Atheroma burden and vascular function

There is emerging evidence that there are gender- differences in the atherosclerotic process and the mechanisms underlying ischemic heart disease. Recent data support a sex-specific role for microvascular dysfunction in ischemic heart diseases. Most important findings are listed below:

- Women have more symptoms and physical limitations but less obstructive coronary artery disease then men along the entire spectrum of acute coronary syndromes.

- The syndrome of chest pain without obstructive coronary artery disease is distinctly more common in women than in men.

- In women chest pain symptoms and disability do not correlate with severity of coronary stenoses.

- Young and middle-aged females show higher rates of adverse outcomes after acute MI than men of similar age, despite less severe coronary narrowing, smaller infarcts, and more preserved systolic function.

Given the lower burden of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) and preserved systolic function in women, which contrasts with greater rates of myocardial ischemia and near-term mortality compared with men, we propose the term “ischemic heart disease” as more appropriate specific to women rather than CAD or coronary heart disease (CHD).

Microvascular angina pectoris

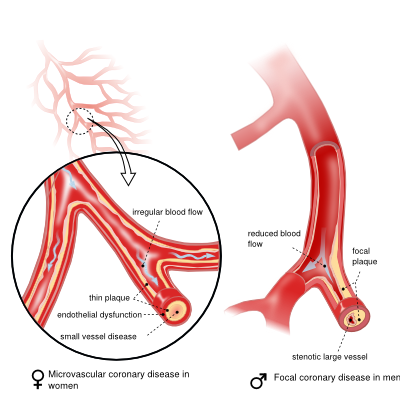

This paradoxical difference, where women have lower rates of anatomical CAD but more symptoms, ischemia, and adverse outcomes, appears linked to abnormal coronary reactivity that includes microvascular dysfunction. Symptoms as the result of microvascular dysfunction should be called microvascular angina. Abnormal coronary reactivity is often the result of diffuse (microvascular) atherosclerosis which is often seen in women, in contrast to the obstructive atherosclerosis which is more common in men (figure 2).

Studies have shown that the plaque morphology changes after menopause. At younger age (<65 yrs) women with an acute myocardial infarction have more often plaques erosions then the classical pattern of plaque rupture and thrombus formation as seen in men. These erosive plaques can cause distal embolization with micro-emboli, leading to endothelial dysfunction of the microvascular beds with angina-like chest pain. This diffuse pattern of atherosclerosis often translates in atypical chest pain.

When obstructive coronary artery is absent these women do not receive the proper preventive medication as the atherosclerosis in the microvasculature progresses, leading to ischemia an possibly fatal arrhythmia’s. After menopause it is known that the microvascular atherosclerosis can progress towards more pronounced atherosclerosis with eventually obstructive plaque formation.

It is this combination of non-obstructive cardiovascular disease with loss of endothelial function in the epicardial and microvascular beds which can lead to chest pain which is not well understood.

For women with evidence of ischemia but no obstructive CAD, anti-anginal and anti-ischemic therapies can improve symptoms, endothelial function, and quality of life; however, trials evaluating impact on adverse outcomes are needed. Women experience more adverse outcomes compared with men because obstructive CAD remains the current focus of therapeutic strategies. Continued research is indicated to devise therapeutic regimens to improve symptom burden and reduce risk in women with ischemic heart disease.

Syndrome X

Cardiac syndrome X (CSX; differentiated from the metabolic syndrome X) is currently defined by typical, angina like chest pain without flow-limiting stenoses on coronary angiography and exclusion of non-cardiac chest pain. Microvascular angina is more prevalent in women then in men. There is a whole range of factors that contribute to the dysfunction of the microvascular beds:

- Distal embolization of erosive plaques

- Chronic inflammation

- Spasm which is often a result of disfunctional smooth muscle cells

- Smoking, hypertension and dyslipidemia can result in endothelial dysfunction

Risk Factors

Risk estimates associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors are overall similar in women and men across various regions of the World. However, the increased risk associated with hypertension and diabetes and the protective effect of exercise and alcohol appear to be larger in women than in men.7 It is also important to make a difference between pre and post menopausal status. Table 1 gives an overview of the global cardiovascular risk factors in women

Smoking

Smoking is the single most important preventable cause of IHD in women. It is a relatively large risk factor for myocardial infarction in women under the age of 55 when compared to men. Smoking enhances the inflammatory process, activates the coagulation system en promotes LDL oxidation. Smoking leads to down-regulation of the estrogen receptor in the endothelial wall leading to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. The combination of smoking and the use of oral contraceptives has a synergistic effect by inducing endothelial dysfunction and activation of the coagulation system. After cessation the risk declines rapidly.

Hypertension

Hypertension is a highly prevalent risk factor that becomes more common in women then in men and is particularly prevalent among black women.7 After menopause the renine activity in plasma increases which leads to sodium retention. By the age of 60 almost 50% of all women have clinically manifest hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg.6 Hypertension in women compared to men more often leads to CVA, left ventricular hypertrophy en diastolic dysfunction. The structural changes of the myocardium can become clinical manifest by dyspnea, supraventricular tachycardia such as atrial fibrillation, angina due to endothelial dysfunction. Slightly elevated blood pressure leads in women more then in men to endothelial dysfunction.6 Hypertension is 2 to 3 times more common in women taking oral contraceptives, especially among obese and older women. Blood pressure lowering strategies have demonstrated to reduce the risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke

Dyslipidemia

In women there is a stronger fluctuation of lipid levels throughout life. Due to hormonal changes total and LDL cholesterol levels increase with an average of 10-14% after menopause.6 Low HDL and high triglycerides seems to be more important risk factors in women than in men. Data from the Nurses Health Study shows that HDL was the lipid parameter that best discriminated the risk of ischemic heart disease.7 Hypertriglyceridemia is associated with a 37% increase in CVD risk in women compared to 14% in men.7 The dynamic changes of the lipidprofiles due to age and menopausal status play an important role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women.

Obesity

Obesity is an important risk factor for diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. There is a gradient of coronary risk with increasing overweight, with the heaviest category of women having a four-fold increased risk for CVD compared with lean women. Around menopause there is a shift from gynoid fat distribution to android. This central obesity in women leads more than in men to the metabolic syndrome, with an increased relative risk of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and hypertension.

Diabetes

Diabetes is associated with a higher risk for ischemic heart disease in women than in men (RR2.0). This is partly due to a higher rate of coexisting risk factors in women with diabetes compared to men. Another important factor is that diabetes is more difficult to treat since less women reach treatment goals when compared to men. In women diabetes is an independent risk factor for developing heart failure. Diabetes during pregnancy has a 7-12 fold risk for developing diabetes later in life.

Women specific risk factors

Estrogens improve the arterial wall response to injury and inhibit the development of atherosclerosis by promoting re-endotheliazation, inhibiting smooth muscle cell proliferation and matrix deposition following vascular injury. They also have a vasodilative effect. Premenopausal women with hormonal dysfunction and estrogen deficiency have a higher risk for developing premature atherosclerosis.6 The polycystic ovarian syndrome, a condition also known as PCOS have a high risk for developing the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes and are therefore an at risk population. Also women with premature ovarian failure (menopause before the age of 40) have a higher risk for developing CVD.

“Novel” risk factors

In an effort to make a more accurate estimation of cardiovascular risk, more than 100 new risk markers have been proposed. There is however a slight resistance to use these markers since the lack of evidence that they really make risk estimation more accurate. A recent summary of systematic reviews conducted for the United States Preventive Services Task force has reviewed the evidence of 9 novel risk factors (Table 1). Of the risk markers evaluated C-reactive protein was the best candidate for screening, however, evidence is still lacking to recommend routine use. The Reynolds Risk score, which is a risk score specifically designed for women, incorporated CRP which reclassified 15 % of the intermediate risk women to high risk.

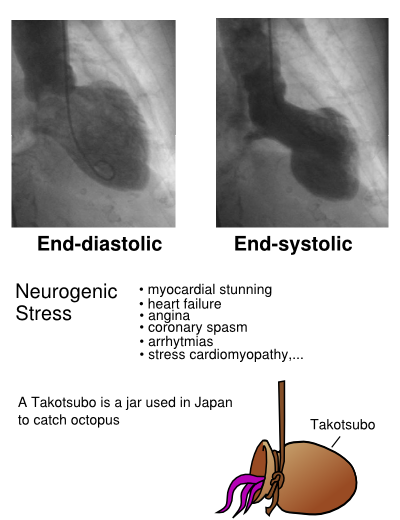

Depression & Acute stress

Data from the INTERHEART study shows, that particular in women the combined exposure psychological risk factors such as depression, chronic emotional distress and acute stress such as major live events, are significantly associated with acute myocardial infarction (OR 2.6 in men and 3.5 in women). A stress-induced condition known as “Takotsubo cardiomyopathy” is almost exclusively seen among women. Due to severe emotional stress these women present with symptoms mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Also the ECG and echocardiogram show all the signs of infarction. However the CAG is often normal with no signs of coronary obstruction. The severe impaired left ventricular function usually normalizes completely after a couple of months.

Risk Factor Assessment

Which risk factors should be assessed?

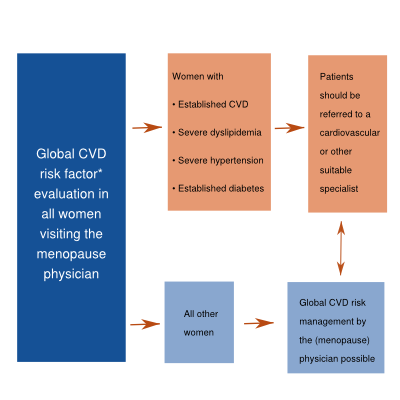

Global cardiovascular risk should be assessed in ALL women in menopause consulting the physician.

Many women appear healthy with no symptoms of CVD nevertheless, they are potentially at increased risk

The following risk factors should be assessed

- Age

- Blood pressure

- Total plasma cholesterol

- Cigarette smoking

Other important information to establish:

- Personal and family history of cardiovascular disease

- Gynecological and obstetric history, including age at menopause

- Body weight

- Waist circumference

- Diet

- Alcohol consumption

- Physical fitness

- Fasting plasma low density (LDL) cholesterol

Additional parameters to consider are:

- Fasting plasma glucose

- 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (advisable in high risk patients or in those with abnormal fasting plasma glucose

- Fasting plasma high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

- Fasting plasma triglycerides

Which patients can be managed for global cardiovascular risk by a menopause physician?

- A woman with a high-risk profile or overt cardiovascular disease requires intensive management including drug therapy

- Collaboration with a cardiovascular specialist is essential if global cardiovascular risk is high, or if cardiovascular disease is present.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of cardiac complaints differ between men and women. Female patients as well as their treating physicians often do not recognize or interpret their complaints as heart problems. Women present less typical as what we are used when men present with heart problems. Typical symptoms, as we have learned from our male patients, such as heavy pressure on the chest which radiates to the left arm or the jaws are often absent in women. Women more often present with complaints such as “tightness”, “out of breath” en “tiredness”. When women get older (>60 yrs) and the risk of obstructive coronary artery disease rises, the clinical presentation becomes more typical (substernal pain, with radiation to jaw and/or left arm).

As a result women are often not recognized and do not receive the proper preventive medication. This could in part explain the higher mortality of cardiovascular diseases in women.

Women who are diagnosed with non cardiac chest pain have twofold increased risk to develop a coronary event in the next 5-7 years and have a four times higher risk for re-hospitalization. This implicates that diagnostic testing is limited and that women should be more aggressively treated for their risk factors.

Chest pain syndromes are more common in women then in men and are less related to the presence of atherosclerosis in the epicardial coronary arteries.8

There are no gender-specific criteria for the interpretation of ECG’s. Non specific ECG changes at rest, a lower exercise capacity and a smaller vessel size contribute to the lower sensitivity and specificity of non-invasive testing in women. At younger ages, endogenous estrogen level scan induce ECG changes mimicking ischemia.

Chest pain complaints in women should always be related to their risk factor profile. It should also be noted that in women, very often chest pain is related to not well regulated hypertension. Blood pressure changes increase vascular wall pressure of the coronary arteries which translates in chest discomfort often at rest. In addition hypertension more often leads to diastolic dysfunction in women en hypertrophy which can result in chest pain. A small dose of nitrates can be effective.

Treatment

Symptom management in patients with non-obstructive cardiovascular disease is a challenge. Important to differentiate between vasospastic forms and complaints related to endothelial dysfunction. Table 2 gives an overview of current treatment options.

Lifestyle behaviors can prevent and reduce the risk of getting heart disease and should therefore be primary focus in the GP-practice. Strategies adapt health lifestyle changes are listed below Adapted from Assessment and Management of cardiovascular risk in women ESC/ESH/2007):9

Smoking: TARGET: permanently stop smoking all forms of tobacco

- Explain detrimental effects

- Assess the degree of addiction and readiness to cease smoking

- Gain commitment

- Establish a smoking cessation strategy (nicotine replacement, counseling and/or pharmacological intervention

- Arrange a schedule of follow up visits to monitor progression.

Diet: TARGET: Adopt healthy diet

- Explain importance of a varied diet and the need to adjust energy intake to achieve and maintain ideal body weight.

- Encourage the consumption of:

- Fruits and vegetables (the five-a-day guideline)

- Whole grain cereal and bread

- Low-fat dairy products

- Fish, especially those rich in omega-3

- Lean meat

- Total fat intake should be no more than 30% of energy intake, with saturated fats comprising in one third of total fat intake.

- Total cholesterol intake < 300mg/day

- Help to identify Foods that are high in saturated fats and cholesterol in order to reduce or remove them.

- Suggest replacement of saturated fats with complex carbohydrates, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats from vegetables and fish.

- Stress the importance of avoiding Foods containing high levels of salt. Reduce overall intake of salts.

Physical Fitness: TARGET: Undertake regular physical exercise

- Explain health benefits of increased physical activity (regain and maintain energy levels, improvement of lipid levels, managing bodyweight, relieving stress)

- Encourage to increase physical activity by climbing stairs, walking or cycling

- The standard for physical activity is > 30 minutes of moving activity for 7 days per week

- A health women should exercise at 60-75% of the average maximum heart rate

Obesity: TARGET: Body Mass Index < 25 kg.m2 or waist circumference < 88

- Explain that by consuming 500-1000 calories/day less than required to maintain the current weight, she can lose about 500 grams/week and ultimately achieve weight loss of 5-15%

- Stress that regular exercise assists in weight loss

- Give diet advice (as described earlier)

Lipids (table 3)

Elevated lipid levels are a significant cardiovascular risk factor. Due to hormonal changes in menopause, total and LD cholesterol levels rise by approximately 10-14%. A low HDL cholesterol as well as high triglycerides is a stronger risk factor for CVD then in men. HDL and triglycerides play an important role in the metabolic syndrome. Women in menopause have an increased risk of developing the metabolic syndrome. This is partly due to the changes in body weight and the distribution of fat tissue since there is a shift from gynoid tot android fat distribution. HDL is hardly influenced by menopause. The dynamic changes in lipid profiles remain an important point in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women.

Bloodpressure (table 4)

In women, after the age of 55 the systolic blood pressure rises. After menopause plasmarenine levels increase and there is an increase in the sensitivity for salt. By the age of 60 more then half of all women have clinically manifest hypertension (defined as a blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg). In women hypertension is more often associated with CVA, left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. These structural changes can give an array of complaints such as dyspnea, palpitations and chest pain.

Post-menopausal hormone therapy

The initation or continuation of hormone replacement therapy should be decided according to the individual patient. Given the many potentially beneficial effects of estrogens on cardiovascular physiology, much expectation was placed on hormone therapy for CVD prevention. However several studies did not support beneficial effects of hormone therapy and in the WHI study (women's health initiative) the study was terminated due to a small increase in CVD. In a woman < 60 years, who recently menopaused with menopausal symptoms and without CVD, the initiation of replacement therapy does not cause early harm. If a woman is at increased risk, HRT therapy is safe to use in the younger women with indications. It should be notes however, that HRT should not be initiated solely for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and should not be regarded as a substitute for antihypertensive treatment.

Conclusions

- Cardiovascular disease in women is the number 1 cause of death in the Western World.

- Cardiovascular risk increases after menopause, regardless of the age it occurs.

- Women share similar cardiovascular risk factors however there are important sex differences in the prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis and coronary vascular physiology.

- There are gender differences in the regulation of vasomotor function of microvessels.

- Women more often have chest pain by less obstructive coronary artery disease.

- In women with persistent chest pain with the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease treatment of symptoms en risk factors is essential.

- The GP or menopause physician plays an important role in the identification of global cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes)

- Cardiovascular specialists and menopause physicians must work as a team to assess global risk for the individual woman.

- Atherosclerosis is the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease.

- Prevention and reduction of cardiovascular disease as early as possible must be a priority

Case 1:

| Case 1: 60- year old woman with risk factor (mis)management | |

|---|---|

| Patient presented at the emergency room with atypical complaints. She was nauseaus had a burning sensation in the chest. She had consulted her GP several times with atypical chest pain. No further action was taken then. | |

| History: | Several weeks of extreme tiredness, burning chest pains, not related to exercise. |

| Risk factors: | Her father had his First heart attack at age 50. She had hypertension during both pregnancies. Menopausa She menopaused at age 46 with a lot of menopausal complaints such as flushes. She had a smoking history of 10 years. |

| Physical examination: | BMI=26, blood pressure: 180/100 mmHg, pulse: 80 r.a., normal heart sounds, grade II/VI systolic murmur. |

| Lab: glucose: | 7 mmol/L, Total cholesterol: 7,1 mmol/L, LDL-cholesterol: 4,5 mmol/L, HDL cholesterol: 0,9 mmol/L, Triglycerides: 2,5 mmol/L. |

| Additional Cardiac Investigation: | ECG showed T-wave inversion in the precordial leads. Cardiac enzymes were positive. Cardiac catheterization showed an 80% stenosis of the left main coronary artery. The echocardiogram show wall segment disorders of the anterior wall and a grad II mitral valve insufficiency. |

| Follow-up: | She received PTCA of the left main en her lipid profile and blood pressure was treated. She recovered and is doing well. |

| Learning points: |

|

Case 2:

| Case 2: 52-year old woman with microvascular disease | |

|---|---|

| Patient is referred for a second opinion to the cardiologist with complaints of tiredness and chest pain. She was evaluated 3 months earlier with chest pain. Cardiovascualr analysis then showed no cardiac pathology. | |

| History: | Patient, who runs every week 10 kilometers, complains that she noticed shortness of breath and tiredness during her weekly run which she describes as abnormal. During running she has no chest pain. She does however experience chest pain, which she describes as “heavy" feeling on the chest, when there is an abrupt change of temperature. Also slight radiation to the left arm. |

| Risk factors: | Menopausal, positive family history, smoking history (she quit 15 years ago), obstetric history normal, Alcohol consumption: 2U/day |

| Physical examination: | BMI=26, blood pressure: 145/90 mmHg, pulse: 70 r.a., normal heart sounds, no murmurs. |

| Lab: glucose: | 5 mmol/L, Total cholesterol: 6,9 mmol/L, LDL-cholesterol: 3,5 mmol/L, HDL cholesterol: 1,3 mmol/L, Triglycerides: 4,5 mmol/L. |

| Additional Cardiac Investigation: | ECG and exercise stress test were completely normal. Vascular scanning of the carotis arteries showed moderatie plaqueformation in de the carotid bulb. No chest pain during exercise. Myocardial perfusion scan showed ischemia in the inferior segments of the heart. Cardiac catheterization: vessel wall irregularities in all coronary arteries, no significant obstructions. |

| Follow-up: | Blood pressure and lipidprofiles was optimized with ACE inhibition and a statine. She was advised to lose weight and drink less alcohol with regard to her elevated triglycerides. She received a low dose b-blocker and was without complaints within 3 months. |

| Learning points: |

|

References

<biblio>

- 1 pmid=20019324

- 2 Steven Allender, Peter Scarborough, Viv Peto and Mike Rayner. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2008. British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group.

- 3 pmid=19788058

- 4 pmid=18036449

- 5 pmid=20160161

- 6 pmid=12575968

- 7 pmid=21159671

- 8 pmid=16908490

- 9 Assessment and Management of cardiovascular risk in women ESC/ESH/2007

</biblio>