Cardiac Arrest

Sébastien Krul, MD

Content is incomplete and may be incorrect. |

Survival of cardiac arrest continues to be very poor. Survival is dependent on the characteristics of the cardiac arrest, on the patient’s medical history, and the time between the cardiac arrest en start of resuscitation. The introduction of the automated external defibrillator (AED) has dramatically increased survival of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims.[1]

Basic Life Support (BLS)

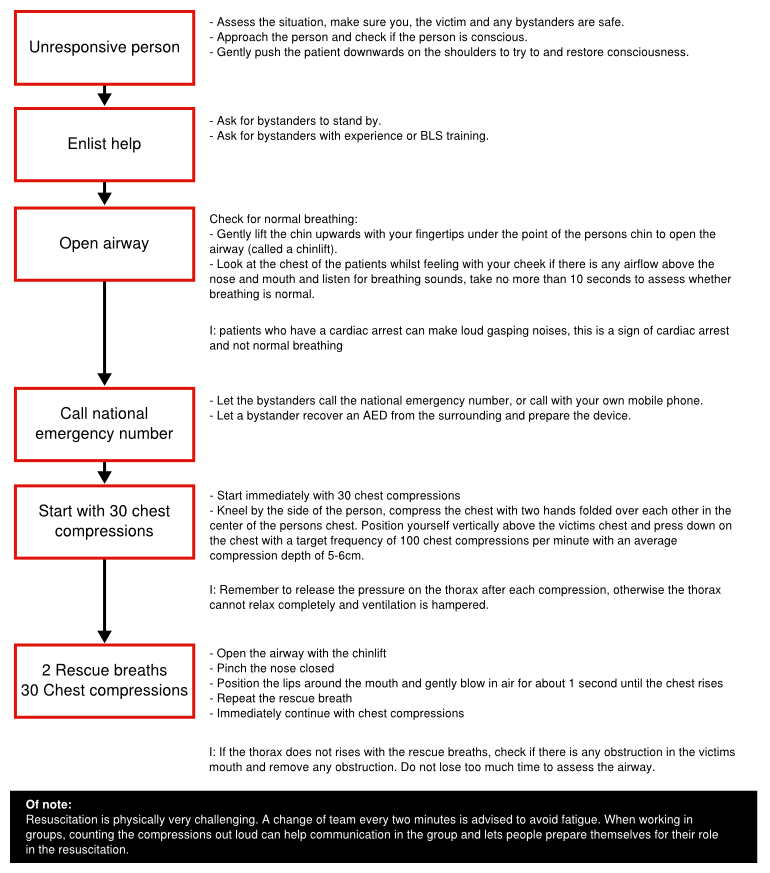

To increase survival after cardiac arrest it is vital to decrease the time to resuscitation. The training of persons in BLS can increase bystander participation in performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). A straightforward protocol has been created to execute BLS. The following steps can be followed to perform BLS.

If at any stage the patient is consciousness, has normal ventilation or recovers consciousness find out what is wrong with the person and get help if needed. Repeated reassessment is necessary to detected deterioration of the patients condition.

Automatic external defibrillator (AED)

The automatic external defibrillator is a complex device that analyses the rhythm of patients and can deliver a shock to defibrillate patients. It detect whether a patient has ventricular fibrillation or a different arrhythmia. When it detects a shockable rhythm it advises the user to deliver the shock, all settings are automatically adjusted. It also remembers the course of events so that the tracing can be recovered and analysed after the resuscitation.

When the AED is attached during BLS let the AED assess the rhythm. Do not manipulate the person while the AED assess the rhythm to prevent motion artefact disturbing the detection algorithm. Follow the instructions of the AED, this can be either a shock or no shock. After shock or non-shock immediately continue with chest compressions and rescue breaths. Continue the CPR until the AED rechecks the rhythm.

Advanced Life Support (ALS)

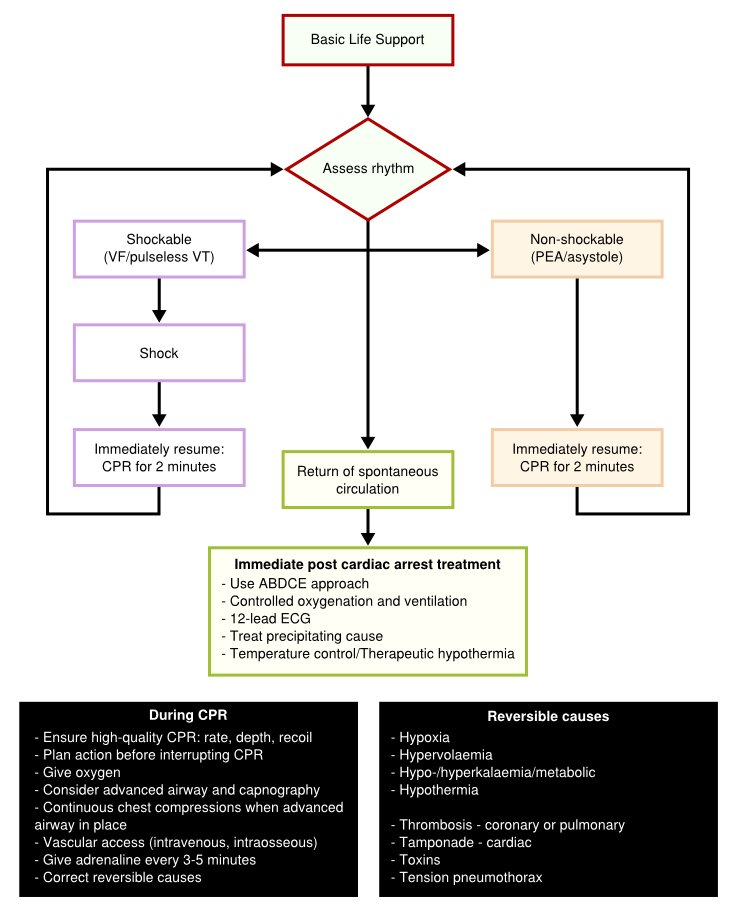

BLS the cornerstone to the treatment of cardiac arrest. Early and high quality CPR is critical to survival. In the hospital setting trained experts and technical equipment can facilitate cardiac arrest management. The only intervention besides proper BLS and early defibrillation to increase survival is the administration of adrenaline. The ALS protocol deviates into two strategies encountered in the setting of cardiac arrest; a shock protocol and no-shock protocol. During both protocols it is important to establish intravascular access as soon as possible, as an alternative intraosseous injection of drugs can be performed. Furthermore assessment of airway management and ventilation is essential. Oxygen should be administered as soon as possible and be titrated to the arterial blood oxygen saturation. Tracheal intubation is the optimal method of providing and maintaining a clear and secure airway. Intubation should be performed by experienced personnel to reduce complications and delay between intubation and chest compressions. When there is return of spontaneous circulation the resuscitation team should stabilize the patient to prevent recurrence of cardiac arrest.

Shock protocol

When a shockable rhythm is detected, it is important to minimize the time between chest compressions and defibrillation. When the shock is delivered immediately resume with the chest compressions to minimize delay. Even after a successful shock the heart can be stunned and effective circulation can only be maintained through chest compressions. After the first round of shock and compressions reassess rhythm and act according to the protocol. After the third shock has been given, adrenaline 1mg and amiodarone 300mg can be administered intravenously. Further adrenaline 1mg can be administered every 3-5 minutes, there is no further indication for anti-arrhythmic drugs during resuscitation.

No-shock protocol

When asystole or pulseless electrical activity is detected CPR should be started immediately simultaneously with 1mg intravenous adrenaline. Assess the rhythm after 2 minutes of chest compressions and continue according to the rhythm. Continue with adrenaline injections intravenously every 3-5 minutes if no return of spontaneous circulation has been achieved. There is no place for further medical intervention.

Post-cardiac arrest treatment

After cardiac arrest and return of spontaneous circulation the whole body ischemia/reperfusion affects all organ systems. Multiple organ failure, increased risk of infection, neurocognitive dysfunction and myocardial dysfunction are common problems encountered after a cardiac arrest which resembles the problems encountered with sepsis. After resuscitation strict control of oxygenation, cardiac output and glucose metabolism can improve outcome after cardiac arrest. Studies have indicated that a period of 12-24 h after cardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia (32-34oC) can increase neurological outcome. This can be achieved by internal infusion or external cooling. Cooling should be initiated quickly after return of circulation. When cooled the temperature should be maintained without to much fluctuations. Warming of the patient should occur very slowly (0.25oC to 0.5oC per hour) to prevent rapid plasma electrolyte concentration, intravascular volume and metabolic rate changes.

Prognosis after cardiac arrest

Prognosis after cardiac arrest is difficult and cannot be fully predicted. Survival after cardiac arrest is poor, mainly due to neurological damage. Clinical examination of the patient can give information on the prognosis of the patient after cardiac arrest. The absence of both pupillary light and corneal reflex at >72h predicts poor outcome. In patients that are not treated with therapeutic hypothermia absence of vestibulo-ocular reflexes at >24h and a Glasgow coma scale motor score of 2 or less >72 are possible prognostic markers of a worse outcome. Furthermore myoclonal status is associated with poor outcome, but recovery can occur, and is therefore not useful in determining the prognosis. Electrophysiological studies measuring somatosensory evoked potentials after 24 hours, absence of N20 cortical response to median nerve stimulation predicts a poor outcome.

Special circumstances

In all circumstances the normal protocol for BLS and ALS is the cornerstone in the treatment of cardiac arrest. However some conditions encountered during resuscitation or as a cause of cardiac arrest, can affect the procedure.

- Anaphylaxis: Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction and can be accompanied by airway/breathing/circulation problems due to swelling of the mucosa. The cause of the anaphylaxis should be identified and patients should receive intramuscular adrenaline before an intravenous route is established and anti-inflammatory drugs (steroids, anti-histamines) should be initiated.

- Asthma: The main troubles encountered in the resuscitation of patients with asthma relates to the underlying lung disease. In general increased lung resistance makes ventilation of these patients difficult and can increase the risk of gastric inflation. Early intubation is indicated in these patients. Due to the hyperinflation of the lungs more energy might be required in defibrillating these patients, as the heart is isolated by air.

- Cardiac arrest after cardiac surgery: Cardiac arrest after cardiac surgery is usually caused by specific causes possibly related as a consequence of the cardiac surgery. Early resternotomy can be the key to survival, especially after repeated defibrillation has failed or if asystole is observed.

- Drowning: Drowning is a common cause of accidental death. Correction of hypoxia is critical in the outcome of these victims. Care should be taken to start immediate resuscitation and restore oxygenation, ventilation and perfusion.

- Electrocution: Electrocution can result in multi-system injury and usually occur in the workspace in adult or at home in children. The direct effects of an electric shock on tissues, for instance paralysis of the respiratory system or muscles, VF in the myocardium, ischemia due to coronary artery spasm or asystole can result in a cardiac arrest. Electrical burns can complicate the resuscitation and care should be taken to avoid further complications resulting from these burns. Adequate fluid therapy is required if there is significant tissue destruction.

- Electrolyte disorder: Electrolyte abnormalities are commonly potassium disorders. During cardiac arrest treatment of these abnormalities is no different than in the normal clinical setting.

- Hyperthermia: Exogenous or endogenous hyperthermia can result in heat stress, progressing to heat exhaustion and results in heat stroke. Heat stroke can lead to varying levels of organ dysfunction accompanied by mental changes. Rapid cooling of the victim should occur as soon as possible.

- Hypothermia: In hypothermia (<35oC) it is difficult to detect signs of life. Therefore resuscitation should proceed according to standard protocols. Resuscitation during hypothermia is difficult, the thorax is stiff and the heart is less responsive to medication. Furthermore drug metabolism is slowed, resulting in increased plasma levels of medication. Medication should be administered at double intervals. As a result of rewarming vasodilatation occurs and fluid administration may be required. Rhythm disturbances usually seen after hypothermia are bradycardia, atrial fibrillation followed by VF and asystole. Second to resuscitation warming of the body temperature by external and internal methods should be started.

- Poisoning: Accidental poisoning in children or by therapeutic or recreational drugs in adults are the main causes of poisoning. Respiratory arrest is more common after poisoning. Early intubation can prevent pulmonary aspiration. Care should be taken when performing mount-to-mouth ventilation in the presence of certain chemical types of poisoning.

- Pregnancy: If a cardiac arrest occurs during pregnancy the safety of the fetus should always be considered. Due to the growth of the uterus compression of the inferior vena cava can occur and as a result venous return and cardiac output is compromised. Furthermore the increased abdominal pressure can increase the risk of pulmonary aspiration and can hamper proper ventilation; therefore early intubation can lower risks and ease cardiopulmonary resuscitation. An emergency hysterotomy or caesarean section needs to be considered, if gestational age is after 20 weeks. After 20 weeks the size of the uterus is large enough to compromise cardiac output.

- Traumatic Cardiorespiratory Arrest: Blunt trauma can cause commotio cordis if there is an impact to the chest wall over the heart. This impact can cause arrhythmias and is sometimes seen during sports. Penetrating trauma can be cause for and emergency thoracotomy. It is important to treat the resuscitation according to protocol and treat reversible causes.

References

<biblio>

- Nolan pmid=20956052

- Koster pmid=20956051

- Deakin pmid=20956050

- Deakin pmid=20956049

- Arntz pmid=20956048

- Biarent pmid=20956047

- Richmond pmid=20956046

- Soar pmid=20956045

- Soar pmid=20956044

- Lippert pmid=20956043

- Hazinski pmid=20956250

- Nadkarni pmid=20956250

- Morley pmid=20956251

- Billi pmid=20956252

- Sayre pmid=20956253

- Jacobs pmid=20956254

- Shuster pmid=20956255

- Morrison pmid=20956256

- O'Connor pmid=20956257

- Camm AH, Fuster TF. Serruys PW. The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN:0199566992

- Nolan pmid= Nolan JP, Soar J, Zideman DA, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Deakin C, Koster RW, Wyllie J, Böttiger B.;ERC Guidelines Writing Group. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 1. Executive summary. Resuscitation. 2010 Oct;81(10):1219-76.