Chest Pain / Angina Pectoris: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

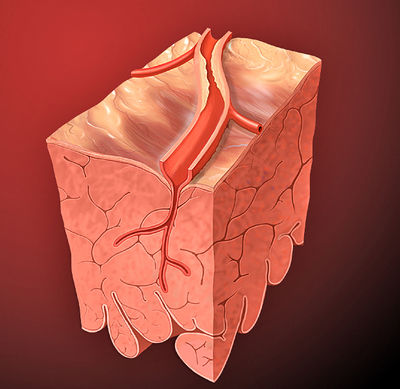

[[File:Heart_coronary_artery.jpg|thumb|400px|An epicardial coronary artery with a atherosclerotic narrowing]] | |||

Stable angina (pectoris) is a clinical syndrome characterized by discomfort in the chest, jaw, shoulder, back, or arms, typically elicited by exertion or emotional stress and relieved | Stable angina (pectoris) is a clinical syndrome characterized by discomfort in the chest, jaw, shoulder, back, or arms, typically elicited by exertion or emotional stress and relieved | ||

by rest or nitroglycerin. It can be attributed to myocardial ischemia which is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic coronary artery disease or aortic valve stenosis. | by rest or nitroglycerin. It can be attributed to myocardial ischemia which is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic coronary artery disease or aortic valve stenosis. | ||

| Line 10: | Line 9: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

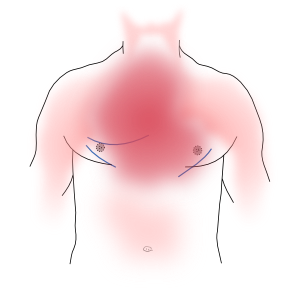

[[File:Chest_pain_areas.svg|thumb|Typical chest pain is retrosternal. Pain may radiate to the arms, jaw, and / or back.]] | |||

Patients often describe angina pectoris as pressure, tightness, or heaviness located centrally in the chest, and sometimes as strangling, constricting, or burning. The pain often radiates elsewhere in the upper body, mainly arms, jaw and/or back. <Cite>REFNAME3</Cite> Some patients only complain about abdominal pain so the presentation can be aspecific. <Cite>REFNAME4</Cite>, <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | Patients often describe angina pectoris as pressure, tightness, or heaviness located centrally in the chest, and sometimes as strangling, constricting, or burning. The pain often radiates elsewhere in the upper body, mainly arms, jaw and/or back. <Cite>REFNAME3</Cite> Some patients only complain about abdominal pain so the presentation can be aspecific. <Cite>REFNAME4</Cite>, <Cite>REFNAME5</Cite> | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Depending on the characteristics, chest pain can be identified as typical angina, atypical angina or non-cardiac chest pain, see Table 1. | Depending on the characteristics, chest pain can be identified as typical angina, atypical angina or non-cardiac chest pain, see Table 1. | ||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" width=" | {| class="wikitable" border="1" width="600px" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! align="center" colspan="2" | Table 1. Clinical classification of chest pain <Cite>REFNAME17</Cite> | ! align="center" colspan="2" | Table 1. Clinical classification of chest pain <Cite>REFNAME17</Cite> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

*Substernal chest discomfort of characteristic quality and duration | *Substernal chest discomfort of characteristic quality and duration | ||

*Provoked by exertion or emotional stress | *Provoked by exertion or emotional stress | ||

*Relieved by rest and/or | *Relieved by rest and/or nitroglycerine | ||

|- | |- | ||

| valign="top"|Atypical angina (probable) | | valign="top"|Atypical angina (probable) | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

The classification of chest pain in combination with age and sex is helpful in estimating the pretest likelihood of angiographically significant coronary artery disease, see Table 2. | The classification of chest pain in combination with age and sex is helpful in estimating the pretest likelihood of angiographically significant coronary artery disease, see Table 2. | ||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" | {| class="wikitable" border="1" width="600px" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! align="left" colspan = "7" | Table 2. | ! align="left" colspan = "7" | Table 2. Clinical pre-test probabilities <sup>a</sup> in patients with stable chest pain symptoms. <Cite>REFNAME20</Cite> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center"| | ||

| align="center" colspan="2" | | | align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Typical angina</b> | ||

| align="center" colspan="2" | Atypical | | align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Atypical angina</b> | ||

| align="center" colspan="2" | | | align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Non-anginal pain</b> | ||

|- | |||

! Age | |||

! Men | |||

! Women | |||

! Men | |||

! Women | |||

! Men | |||

! Women | |||

|- | |||

! 30-39 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 59 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 28 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 29 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | 10 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 18 | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | 5 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | ! 40-49 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 69 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 37 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 38 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | 14 | ||

| align="center" | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 25 | ||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | 8 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | ! 50-59 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 77 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 47 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 49 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 20 | ||

| align="center" | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 34 | ||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | 12 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | ! 60-69 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 84 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 58 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 59 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 28 | ||

| align="center" | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 44 | ||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 17 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | ! 70-79 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FF69B4" | 89 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 68 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 69 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 37 | ||

| align="center" | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 54 | ||

| align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 24 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | | ! >80 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FF69B4" | 93 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 76 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#FFCCCC" | 78 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 47 | ||

| align="center" | | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 65 | ||

| | | align="center" bgcolor="#F0F8FF" | 32 | ||

|- | |||

| colspan = "7" bgcolor="#FFFFFF"| | |||

|- | |||

! colspan = "7" | ECG = electrocardiogram; PTP = pre-test probability; SCAD = stable coronary artery disease. | |||

|- | |||

| colspan = "7" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b><sup>a</sup></b> Probabilities of obstructive coronary disease shown reflect the estimates for patients aged 35, 45, 55, 65, 75 and 85 years. | |||

*Groups in <i>white boxes</i> have a PTP <15% and hence can be managed without further testing. | |||

*Groups in <i>blue boxes</i> have a PTP of 15–65%. They could have an exercise ECG if feasible as the initial test. However, if local expertise and availability permit a non-invasive imaging based test for ischaemia this would be preferable given the superior diagnostic capabilities of such tests. In young patients radiation issues should be considered. | |||

*Groups in <i>light pink boxes</i> have PTPs between 66–85% and hence should have a non-invasive imaging functional test for making a diagnosis of SCAD. | |||

*In groups in <i>dark pink boxes</i> the PTP is >85% and one can assume that SCAD is present. They need risk stratification only. | |||

|} | |} | ||

The severity of complaints can be classified according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society as shown in Table 3 | The severity of complaints can be classified according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society as shown in Table 3 | ||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" | {| class="wikitable" border="1" width="600px" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="2" | Table 3. Classification of angina severity according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society | ! colspan="2" | Table 3. Classification of angina severity according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society | ||

|- | |- | ||

! width="100"| ''Class'' | |||

| ''Level of Symptoms'' | |||

|- | |- | ||

! valign="top"| Class I | |||

| 'Ordinary activity does not cause angina' | |||

Angina with strenuous or rapid or prolonged exertion only | Angina with strenuous or rapid or prolonged exertion only | ||

|- | |- | ||

! valign="top"| Class II | |||

| 'Slight limitation of ordinary activity' | |||

Angina on walking or climbing stairs rapidly, walking uphill or exertion after meals, in cold weather, when under emotional stress, or only during the first few hours after awakening | Angina on walking or climbing stairs rapidly, walking uphill or exertion after meals, in cold weather, when under emotional stress, or only during the first few hours after awakening | ||

|- | |- | ||

! valign="top"| Class III | |||

| 'Marked limitation of ordinary physical activity' | |||

Angina on walking one or two blocks on the level or one flight of stairs at a normal pace under normal conditions | Angina on walking one or two blocks on the level or one flight of stairs at a normal pace under normal conditions | ||

|- | |- | ||

! valign="top"| Class IV | |||

| 'Inability to carry out physical activity without discomfort' or 'angina at rest' | |||

|} | |} | ||

During angina pectoris ‘vegetative’ symptoms can occur, including sweating, nausea, paleface, anxiety and agitation. This is probably caused by the autonomic nerve system in reaction to stress. <Cite>REFNAME9</Cite> | During angina pectoris ‘vegetative’ symptoms can occur, including sweating, nausea, paleface, anxiety and agitation. This is probably caused by the autonomic nerve system in reaction to stress. <Cite>REFNAME9</Cite> | ||

Finally, it is important to differentiate unstable angina (indicating an acute coronary syndrome or even myocardial infarction requiring urgent treatment) from stable angina. Unstable angina typically is severe, occurs without typical provocation and does not disappear with rest, and has a longer duration than stable angina. It is important to initiate prompt treatment in these patients, as described in the acute coronary syndromes chapter. | Finally, it is important to differentiate unstable angina (indicating an acute coronary syndrome or even myocardial infarction requiring urgent treatment) from stable angina. Unstable angina typically is severe, occurs without typical provocation and does not disappear with rest, and has a longer duration than stable angina. It is important to initiate prompt treatment in these patients, as described in the acute coronary syndromes chapter. | ||

==Physical Examination== | ==Physical Examination== | ||

| Line 131: | Line 157: | ||

==Stress Testing in Combination with Imaging== | ==Stress Testing in Combination with Imaging== | ||

Some patients are unable to perform physical exercise. Furthermore, in patients with resting ECG abnormalities the exercise ECG is associated with low sensitivity and specificity. If the ECG made during exercise testing does not show any abnormalities myocardial ischemia becomes unlikely as cause of the complaints. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, the following additional tests may be performed. | Some patients are unable to perform physical exercise. Furthermore, in patients with resting ECG abnormalities the exercise ECG is associated with low sensitivity and specificity. | ||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" width="600px" | |||

|- | |||

|colspan = "7" | <b>Table 4. Characteristics of tests commonly used to diagnose the presence of coronary artery disease. <Cite>REFNAME20</Cite></b> | |||

|- | |||

| bgcolor="#FFFFFF" rowspan="2"| | |||

|align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Diagnosis of CAD</b> | |||

|- | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Sensitivity (%)</b> | |||

| align="center" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | <b>Specificity (%)</b> | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Exercise ECG <sup>a, 91, 94, 95</sup></b> | |||

!45–50 | |||

!85–90 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Exercise stress echocardiography <sup>96</sup></b> | |||

!80–85 | |||

!80–88 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Exercise stress SPECT <sup>96-99</sup></b> | |||

!73–92 | |||

!63–87 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Dobutamine stress echocardiography <sup>96</sup></b> | |||

!79–83 | |||

!82–86 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Dobutamine stress MRI <sup>b,100</sup></b> | |||

!79–88 | |||

!81–91 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Vasodilator stress echocardiography <sup>96</sup></b> | |||

!72–79 | |||

!92–95 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Vasodilator stress SPECT <sup>96, 99</sup></b> | |||

!90–91 | |||

!75–84 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Vasodilator stress MRI <sup>b,98, 100-102</sup></b> | |||

!67–94 | |||

!61–85 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Coronary CTA <sup>c,103-105</sup></b> | |||

!95–99 | |||

!64–83 | |||

|- | |||

| <b>Vasodilator stress PET <sup>97, 99, 106</sup></b> | |||

!81–97 | |||

!74–91 | |||

|- | |||

| colspan="3" bgcolor="#FFFFFF"| <b>CAD</b> = coronary artery disease; <b>CTA</b> = computed tomography angiography; <b>ECG</b> = electrocardiogram; <b>MRI</b> = magnetic resonance imaging; <b>PET</b> = positron emission tomography; <b>SPECT</b> = single photon emission computed tomography. | |||

|- | |||

| colspan="3"|<b><sup>a</sup></b> Results without/with minimal referral bias. | |||

<b><sup>b</sup></b> Results obtained in populations with medium-to-high prevalence of disease without compensation for referral bias. | |||

<b><sup>c</sup></b> Results obtained in populations with low-to-medium prevalence of disease. | |||

|} | |||

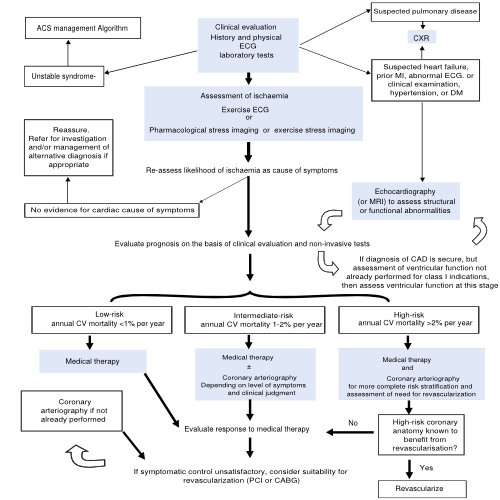

[[File:Algorithm_for_the_initial_evaluation_of_patients_with_clinical_symptoms_of_angina.svg|thumb|right|500px|Figure 1. Algorithm for the initial evaluation of patients with clinical symptoms of angina]] | |||

If the ECG made during exercise testing does not show any abnormalities myocardial ischemia becomes unlikely as cause of the complaints. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, the following additional tests may be performed. | |||

#Exercise echocardiography means that an echocardiography is made before and during different stages up to peak exercise in order to identify wall motion abnormalities. <Cite>REFNAME12</Cite> An alternative is pharmacological stress testing using dobutamine. | #Exercise echocardiography means that an echocardiography is made before and during different stages up to peak exercise in order to identify wall motion abnormalities. <Cite>REFNAME12</Cite> An alternative is pharmacological stress testing using dobutamine. | ||

#Myocardium Perfusion Scintigraphy (MPS) is able to show the perfusion of the heart during exercise and at rest based on radiopharmaceutical tracer uptake . <Cite>REFNAME13</Cite> | #Myocardium Perfusion Scintigraphy (MPS) is able to show the perfusion of the heart during exercise and at rest based on radiopharmaceutical tracer uptake . <Cite>REFNAME13</Cite> | ||

#Magnetic Resonance Imaging can be done with vasodilatory adenosine or stimulating dobutamine to detect wall motion abnormalities induced by ischemia during pharmacological stress. <Cite>REFNAME14</Cite> | #Magnetic Resonance Imaging can be done with vasodilatory adenosine or stimulating dobutamine to detect wall motion abnormalities induced by ischemia during pharmacological stress. <Cite>REFNAME14</Cite> | ||

The findings on stress testing can be used to determine the choice between medical therapy only or medical therapy and invasive assessment of the coronary anatomy in patients with stable angina. Coronary angiography is recommended based upon the severity of symptoms, likelihood of ischemic disease, and risk of the patient for subsequent complications including mortality based on risk scores. <Cite>REFNAME15</Cite> For the algorithm for the initial evaluation of patients with clinical symptoms of angina see Figure 1 | The findings on stress testing can be used to determine the choice between medical therapy only or medical therapy and invasive assessment of the coronary anatomy in patients with stable angina. Coronary angiography is recommended based upon the severity of symptoms, likelihood of ischemic disease, and risk of the patient for subsequent complications including mortality based on risk scores. <Cite>REFNAME15</Cite> For the algorithm for the initial evaluation of patients with clinical symptoms of angina see Figure 1. | ||

==Coronoary Angiography== | ==Coronoary Angiography== | ||

| Line 178: | Line 265: | ||

#REFNAME18 pmid=3925741 | #REFNAME18 pmid=3925741 | ||

#REFNAME19 pmid=9355934 | #REFNAME19 pmid=9355934 | ||

#REFNAME20 pmid= | #REFNAME20 pmid=23996286 | ||

</biblio> | </biblio> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:50, 16 September 2013

Stable angina (pectoris) is a clinical syndrome characterized by discomfort in the chest, jaw, shoulder, back, or arms, typically elicited by exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin. It can be attributed to myocardial ischemia which is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic coronary artery disease or aortic valve stenosis.

Three major coronary arteries supply the heart with oxygenated blood, the right coronary artery (RCA), the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and the left circumflex artery (LCx). When the coronary arteries are affected by atherosclerosis and the lumen of the coronary arteries progressively narrow, a dysbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and myocardial oxygen consumption may occur, causing myocardial ischemia. In stable angina this imbalance mainly occurs when oxygen demand increases due to exercise, increased heart rate, contractility or wall stress.

A complete history and physical examination are essential to support the diagnosis (stable) angina pectoris and to exclude other (acute) causes of chest pain such as an acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, arrhythmias, pulmonary embolism, (tension) pneumothorax or pneumonia, gastroesophageal reflux or spams, hyperventilation or musculoskeletal pain. REFNAME2 In addition, laboratory tests and specific cardiac investigations are often necessary.

History

Patients often describe angina pectoris as pressure, tightness, or heaviness located centrally in the chest, and sometimes as strangling, constricting, or burning. The pain often radiates elsewhere in the upper body, mainly arms, jaw and/or back. REFNAME3 Some patients only complain about abdominal pain so the presentation can be aspecific. REFNAME4, REFNAME5

Angina pectoris however has some characteristics that can help to differentiate between other causes of (chest) pain. Angina pectoris is usually is brief and gradual in onset and offset, with the intensity increasing and decreasing over several minutes. The pain does not change with respiration or position. If patients had angina pectoris previously they are often able to recognize the pain immediately. REFNAME6 Angina pectoris is a manifestation of arterial insufficiency and usually occurs with increasing oxygen demand such as during exercise. As soon as the demand is decreased (by stopping the exercise for example) complaints usually disappears within a few minutes. Another way to relieve pain is by administration of nitro-glycerine. Nitro-glycerine spray is a vasodilator which reduces venous return to the heart and therefore decreases the workload and therefore oxygen demand. It also dilates the coronary arteries and increases coronary blood flow. REFNAME7 The response to nitro-glycerine is however not specific for angina pectoris, a similar response may be seen with oesophageal spasm or other gastrointestinal problems because nitro-glycerine relaxes smooth muscle tissue. REFNAME8

Depending on the characteristics, chest pain can be identified as typical angina, atypical angina or non-cardiac chest pain, see Table 1.

| Table 1. Clinical classification of chest pain REFNAME17 | |

|---|---|

| Typical angina (definite) | Meets three of the following characteristics:

|

| Atypical angina (probable) | Meets two of these characteristics |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | Meets one or none of the characteristics |

The classification of chest pain in combination with age and sex is helpful in estimating the pretest likelihood of angiographically significant coronary artery disease, see Table 2.

| Table 2. Clinical pre-test probabilities a in patients with stable chest pain symptoms. REFNAME20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical angina | Atypical angina | Non-anginal pain | ||||

| Age | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 30-39 | 59 | 28 | 29 | 10 | 18 | 5 |

| 40-49 | 69 | 37 | 38 | 14 | 25 | 8 |

| 50-59 | 77 | 47 | 49 | 20 | 34 | 12 |

| 60-69 | 84 | 58 | 59 | 28 | 44 | 17 |

| 70-79 | 89 | 68 | 69 | 37 | 54 | 24 |

| >80 | 93 | 76 | 78 | 47 | 65 | 32 |

| ECG = electrocardiogram; PTP = pre-test probability; SCAD = stable coronary artery disease. | ||||||

a Probabilities of obstructive coronary disease shown reflect the estimates for patients aged 35, 45, 55, 65, 75 and 85 years.

| ||||||

The severity of complaints can be classified according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society as shown in Table 3

| Table 3. Classification of angina severity according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society | |

|---|---|

| Class | Level of Symptoms |

| Class I | 'Ordinary activity does not cause angina'

Angina with strenuous or rapid or prolonged exertion only |

| Class II | 'Slight limitation of ordinary activity'

Angina on walking or climbing stairs rapidly, walking uphill or exertion after meals, in cold weather, when under emotional stress, or only during the first few hours after awakening |

| Class III | 'Marked limitation of ordinary physical activity'

Angina on walking one or two blocks on the level or one flight of stairs at a normal pace under normal conditions |

| Class IV | 'Inability to carry out physical activity without discomfort' or 'angina at rest' |

During angina pectoris ‘vegetative’ symptoms can occur, including sweating, nausea, paleface, anxiety and agitation. This is probably caused by the autonomic nerve system in reaction to stress. REFNAME9

Finally, it is important to differentiate unstable angina (indicating an acute coronary syndrome or even myocardial infarction requiring urgent treatment) from stable angina. Unstable angina typically is severe, occurs without typical provocation and does not disappear with rest, and has a longer duration than stable angina. It is important to initiate prompt treatment in these patients, as described in the acute coronary syndromes chapter.

Physical Examination

There are no specific signs in angina pectoris. Physical examination of a patient with (suspected) angina pectoris is important to assess the presence of hypertension, valvular heart disease (in particular aortic valve stenosis) or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. It should include the body-mass index, evidence of non-coronary vascular disease which may be asymptomatic and other signs of co-morbid conditions. E.g.: absence of palpable pulsations in the dorsal foot artery is associated with an 8 fold increase in the likelihood of coronary artery disease.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

The electrocardiogram (ECG) is an important tool to differentiate between unstable angina (acute coronary syndrome) and stable angina in addition to the patient’s history. Patients with unstable angina pectoris are likely to show abnormalities on the ECG at rest, in particular ST-segment deviations. Although a resting ECG may show signs of coronary artery disease such as pathological Q-waves indicating a previous MI or other abnormalities, many patients with stable angina pectoris have a normal ECG at rest. Therefore exercise ECG testing may be necessary to show signs of myocardial ischemia. REFNAME10

Exercise ECG testing is performed with gradually increasing intensity on a treadmill or a bicycle ergo-meter. Exercise increases the oxygen demand of the heart, potentially revealing myocardial ischemia by the occurrence of ST-segment depression on the ECG. REFNAME11

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory testing in the setting of angina pectoris can be useful to differentiate between different causes of the pain, including an acute coronary syndrome in which there will be elevation of the marker of myocardial necrosis. Anaemia should be ruled out as a cause of ischemia. Renal function is important for pharmacological therapy. Moreover, it might assist in establishing a cardiovascular risk profile.

Stress Testing in Combination with Imaging

Some patients are unable to perform physical exercise. Furthermore, in patients with resting ECG abnormalities the exercise ECG is associated with low sensitivity and specificity.

| Table 4. Characteristics of tests commonly used to diagnose the presence of coronary artery disease. REFNAME20 | ||||||

| Diagnosis of CAD | ||||||

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |||||

| Exercise ECG a, 91, 94, 95 | 45–50 | 85–90 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise stress echocardiography 96 | 80–85 | 80–88 | ||||

| Exercise stress SPECT 96-99 | 73–92 | 63–87 | ||||

| Dobutamine stress echocardiography 96 | 79–83 | 82–86 | ||||

| Dobutamine stress MRI b,100 | 79–88 | 81–91 | ||||

| Vasodilator stress echocardiography 96 | 72–79 | 92–95 | ||||

| Vasodilator stress SPECT 96, 99 | 90–91 | 75–84 | ||||

| Vasodilator stress MRI b,98, 100-102 | 67–94 | 61–85 | ||||

| Coronary CTA c,103-105 | 95–99 | 64–83 | ||||

| Vasodilator stress PET 97, 99, 106 | 81–97 | 74–91 | ||||

| CAD = coronary artery disease; CTA = computed tomography angiography; ECG = electrocardiogram; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PET = positron emission tomography; SPECT = single photon emission computed tomography. | ||||||

| a Results without/with minimal referral bias.

b Results obtained in populations with medium-to-high prevalence of disease without compensation for referral bias. c Results obtained in populations with low-to-medium prevalence of disease. | ||||||

If the ECG made during exercise testing does not show any abnormalities myocardial ischemia becomes unlikely as cause of the complaints. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, the following additional tests may be performed.

- Exercise echocardiography means that an echocardiography is made before and during different stages up to peak exercise in order to identify wall motion abnormalities. REFNAME12 An alternative is pharmacological stress testing using dobutamine.

- Myocardium Perfusion Scintigraphy (MPS) is able to show the perfusion of the heart during exercise and at rest based on radiopharmaceutical tracer uptake . REFNAME13

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging can be done with vasodilatory adenosine or stimulating dobutamine to detect wall motion abnormalities induced by ischemia during pharmacological stress. REFNAME14

The findings on stress testing can be used to determine the choice between medical therapy only or medical therapy and invasive assessment of the coronary anatomy in patients with stable angina. Coronary angiography is recommended based upon the severity of symptoms, likelihood of ischemic disease, and risk of the patient for subsequent complications including mortality based on risk scores. REFNAME15 For the algorithm for the initial evaluation of patients with clinical symptoms of angina see Figure 1.

Coronoary Angiography

Coronary angiography (CAG) can assist in the diagnosis and the selection of treatment options for stable angina pectoris. During CAG, the coronary anatomy is visualized including the presence of coronary luminal stenoses. A catheter is inserted into the femoral artery or into the radial artery. The tip of the catheter is positioned at the beginning of the coronary arteries and contrast fluid is injected. The contrast is made visible by X ray and the images that are obtained are called angiograms. If stenoses are visible, the operator will judge whether this stenosis is significant and eligible for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Treatment

Stable angina pectoris is always treated with medical therapy aimed at reducing risk and at alleviating symptoms. Current guidelines recommend revascularization in patients with persistent symptoms despite optimal medical therapy. REFNAME16 Furthermore, revascularization is indicated in case of large areas of myocardial ischemia (such as a left main stem stenosis, a proximal LAD stenosis or significant three vessel disease) and in the presence of high-risk features such as ventricular arrhythmia, heart failure, widening of QRS during ischemia, axis deviation during ischemia or hypotension during ischemia. The choice between PCI and CABG depends on the coronary anatomy and clinical characteristics and the choice should be made in a team including (interventional) cardiologists and thoracic surgeons.

Medical Therapy

Initial treatment of stable angina pectoris focuses on medication reducing the oxygen demand of the heart. ß blockers lower heart rate and blood pressure. REFNAME17 Nitrates dilatate the coronary arteries and reduce venous return if used to abort an episode of pain. REFNAME18 Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin) reduces the risk of development of a thrombus and thus acute (coronary) ischemic events. REFNAME19 Risk factors like smoking, overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes need to be treated in order to prevent disease progression and future events. See chronic coronary diseases.

PCI

The procedure of PCI is similar to a CAG, except this time a catheter with an inflatable balloon will be brought to the site of the stenosis. Inflation of the balloon within the coronary artery will crush the atherosclerosis and eliminate the stenosis. To prevent collapse of the arteric wall and restenosis, a stent is often positioned at the site of the stenosis.

CABG

With CABG, a bypass is placed around the stenosis using the internal thoracic arteries or the saphenous veins from the legs. The bypass originates proximal from the stenosis and terminates distally from the stenosis. The operation usually requires the use of cardiopulmonary bypass and cardiac arrest, however in certain cases the grafts can be placed on the beating heart (“off-pump” surgery)

References

<biblio>

- REFNAME1 pmid=11756201

- REFNAME2 pmid=4997794

- REFNAME3 pmid=10099685

- REFNAME4 pmid=10866870

- REFNAME5 pmid=10751787

- REFNAME6 pmid=6831781

- REFNAME7 pmid=3925741

- REFNAME8 pmid=14678917

- REFNAME9 pmid=15289388

- REFNAME10 pmid=8375424

- REFNAME11 pmid=17162834

- REFNAME12 pmid=1352191

- REFNAME13 pmid=2007701

- REFNAME14 pmid=12566362

- REFNAME15 pmid=18061078

- REFNAME16 pmid=20802248

- REFNAME17 pmid=16735367

- REFNAME18 pmid=3925741

- REFNAME19 pmid=9355934

- REFNAME20 pmid=23996286

</biblio>