CPVT: Difference between revisions

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

==Genetic diagnosis== | ==Genetic diagnosis== | ||

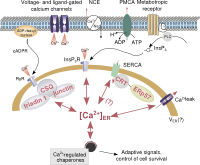

[[Image:CPVT. | [[Image:CPVT.svg|thumb|200px|left|Intraluminal calcium as a primary regulator of endoplasmic reticulum function 2005<cite>CellCalcium</cite>]] | ||

CPVT is caused by mutations in genes involved in the calcium homeostasis of cardiac cells. Four disease-causing genes have been identified: the ryanodine<cite>ryanodine</cite> receptor 2 gene (RyR2) (60%), the cardiac calsequestrin 2 gene (CASQ2) (1-2%), the calmodulin gene (CALM1) (<1%) and the TRDM gene (<1%). Mutant RyR2 channels have a gain-of-function effect, resulting in excessive calcium release during sympathetic activation. Mutant CASQ2 causes loss of buffering capacity for calcium of the sarcoplasmatic reticulum. The mutations cause excessive calcium in the myocyte cytosol generating depolarizing membrane currents, which in turn lead to delayed afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. | CPVT is caused by mutations in genes involved in the calcium homeostasis of cardiac cells. Four disease-causing genes have been identified: the ryanodine<cite>ryanodine</cite> receptor 2 gene (RyR2) (60%), the cardiac calsequestrin 2 gene (CASQ2) (1-2%), the calmodulin gene (CALM1) (<1%) and the TRDM gene (<1%). Mutant RyR2 channels have a gain-of-function effect, resulting in excessive calcium release during sympathetic activation. Mutant CASQ2 causes loss of buffering capacity for calcium of the sarcoplasmatic reticulum. The mutations cause excessive calcium in the myocyte cytosol generating depolarizing membrane currents, which in turn lead to delayed afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. | ||

Revision as of 22:13, 29 December 2013

Auteur: Louise R.A. Olde Nordkamp

Supervisor: Arthur A.M. Wilde

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) refers to a hereditary disease that is associated with exercise (or adrenergic) induced ventricular arrhythmias and/or cardiac syncope and carries an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

General features

- The diagnosis is based on adrenergic-induced bidirectional and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

- The resting ECG is normal and the heart is structurally normal.

- It is an inheritable cardiac arrhythmia syndromearrhythm with an autosomal dominant (RyR2)Priori or recessive (CASQ2) inheritance.

- The arrhythmias typically occur in childrentachycardia and adolescents.

- The mortality rate is approximately 31% by the age of 30 years, if untreated.

- The prevalence is estimated to be 1:10.000 in Europe.

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of CPVT is confirmed in an individual with polymorphic VT reproducibly induced during exercise tests, isoproterenol infusion or emotion and exercise.

Patients present themselves most often with syncope or even an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, usually during the first or second decade of life. The symptoms are always triggered by exercise or emotional stress. A family history of exercise-related syncope, seizure or sudden death is reported in 30% of the patients.

Family members of patients with CPVT who also carry a mutation in a CPVT-associated gene are often asymptomatic.

Physical examination

Patients can present with symptoms of arrhythmias during exercise:

- Out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest

- Syncope, pre-syncope (weakness, lightheadedness, dizziness)

ECG tests

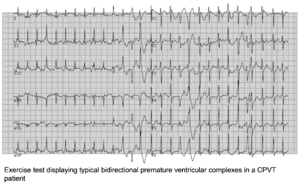

The resting ECG in CPVT is normal. However, there is a progressive ventricular ectopy as heart rate increases during exercise or isoproterenol infusion. Both the frequency and the complexity of the ventricular ectopy increase with the work load. It generally starts with monomorphic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and is followed bigemini and subsequently more complex arrhythmias, including doublets triplets, bidirectional ventricular tachycardia to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Most of the times, the arrhythmia is self-limiting. However, in some patients, especially if exercise is continued, repeated polymorphic VTs can deteriorate in ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death.

Genetic diagnosis

CPVT is caused by mutations in genes involved in the calcium homeostasis of cardiac cells. Four disease-causing genes have been identified: the ryanodineryanodine receptor 2 gene (RyR2) (60%), the cardiac calsequestrin 2 gene (CASQ2) (1-2%), the calmodulin gene (CALM1) (<1%) and the TRDM gene (<1%). Mutant RyR2 channels have a gain-of-function effect, resulting in excessive calcium release during sympathetic activation. Mutant CASQ2 causes loss of buffering capacity for calcium of the sarcoplasmatic reticulum. The mutations cause excessive calcium in the myocyte cytosol generating depolarizing membrane currents, which in turn lead to delayed afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias.

Risk Stratification and Treatment

Risk stratification and treatment is best provided by an expert cardio-genetics cardiologist.

"Lifestyle modification":

- All CPVT patients should avoid competitive and other strenuous exercise

Medication/Other therapies:

- β-blockers are first line therapy in CPVT because of their sympatholytical effect. However, β-blockers are not fully protective in all CPVT patients.

- Flecainideflecainide can be given to CPVT patients with refractory ventricular ectopy despite β-blocker therapy. Flecainide directly blocks RyR2 channels.Werf

- Left cardiac sympathetic denervationWilde can be done in selected patients and largely prevents norepinephrine release in the heart and may therefore reduce adrenergically mediated arrhythmias.

- The need for ICD therapy needs careful judgement since ICDs might not offer the ultimate protection in CPVT because of the fact that both appropriate and inappropriate shocks can trigger catecholamine release, resulting in arrhythmic ICD storms and death.

References

<biblio>

- tachycardia pmid=7867192

- arrhythm pmid=23022705

- flecainide pmid=21616285

- Wilde pmid=18463378

- Werf pmid=20851823

- Priori pmid=12093772

- ryanodine pmid=22787013

- CellCalcium From Denis Burdakova, Ole H. Petersenb, Alexei Verkhratskya Intraluminal calcium as a primary regulator of endoplasmic reticulum function 2005 Cell Calcium

</biblio>