Myocarditis: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

[[Image:Endomyocardial biopsy.png]] | [[Image:Endomyocardial biopsy.png]] | ||

==References== | |||

<biblio> | |||

#Maron pmid=19221222 | |||

#Felker pmid=10760308 | |||

#Kuhl pmid=15699250 | |||

#Bowles pmid=12906974 | |||

#Cooper pmid=19026310 | |||

#Oliveira pmid=7295439 | |||

#McCarthy pmid=10706898 | |||

#Cooper2007 pmid=17959655 | |||

#Abdel-Aty pmid=15936612 | |||

#Friedrich pmid=9603535 | |||

#Mahrholdt2004 pmid=14993139 | |||

#Mahrholdt2006 pmid=17015795 | |||

#Kuhl2003 pmid=12771005 | |||

#Monrad pmid=3698228 | |||

#Wojnicz pmid=11435335 | |||

#Cooper1997 pmid=9197214 | |||

</biblio> | |||

Revision as of 06:32, 1 April 2013

Myocarditis : clinical presentation and management

Maarten Groenink, MD, PhD

Dept. Of Cardiology and Radiology

Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam

Introduction

Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium that may present with sudden cardiac death, symptoms mimicking myocardial infarction, heart rhythm and conduction disorders, and heart failure. Infectious, mostly viral, auto-immune and toxic agents are the main causative factors of myocarditis. The incidence of myocarditis is largely unknown because of difficulties establishing the diagnosis and the lack of a gold standard other than myocardial biopsy, which has a low sensitivity, mostly due to sampling error. In a recent large registry evaluation of sudden cardiac death in 1866 athletes, myocarditis was considered causative in 6 percent of cases. Maron Endomyocardial biopsy revealed myocarditis in 9% of 1230 patients with idiopathic heart failure.Felker As in the ‘myocarditis treatment trial (N Engl J Med 1995 Aug 3;333(5):269-75), the true prevalence of myocarditis is probably underestimated in patients with ‘idiopathic’ heart failure in these studies. This was recently suggested in a study showing high prevalence of viral genomes in myocardial biopsies of 245 patients with unexplained cardiomyopathy (median ejection fraction 35%).Kuhl See Figure 1. Myocarditis may present with a wide variety of symptoms, partly determined by the underlying cause : acute, subacute or chronic. Probably, the majority of viral myocarditis has a subclinical course. It is challenging to provide diagnosis and select appropriate patients for myocardial biopsy, whereas the vast majority of cases require only hemodynamic supportive clinical measures. Magnetic resonance imaging techniques may assist in the management of patients with suspected myocarditis.

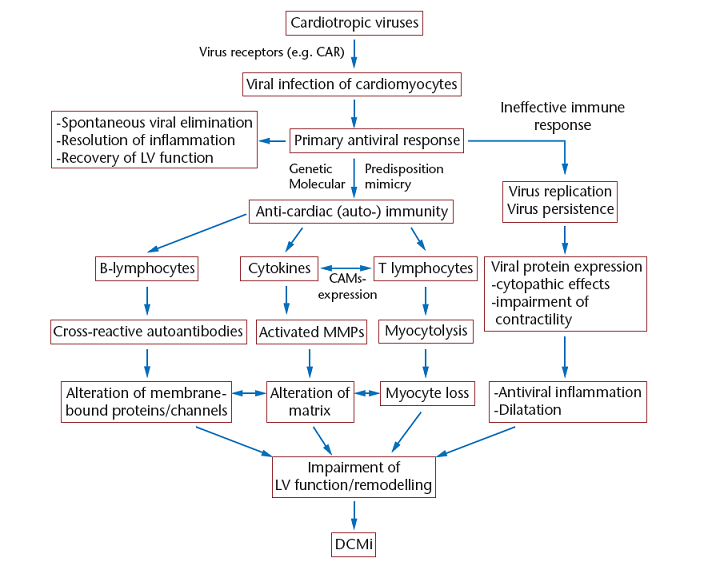

Figure 1 : Viral genomes in myocardial biopsies from patients with unexplained heart failure

Table 1 : causes of myocarditis

Pathogenesis of myocarditis

Myocarditis can be caused by a variety of infectious and noninfectious illnesses (Table 1).

- Viral myocarditis

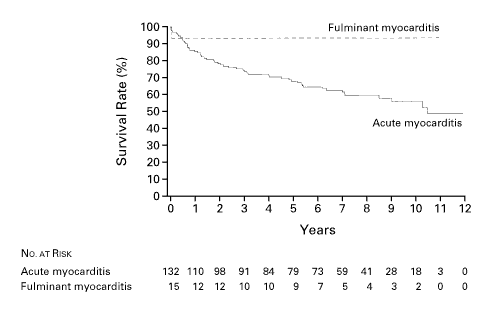

Most often, myocarditis results from common viral infections. In developed countries, the most frequently identified viruses were enteroviruses (including coxsackievirus) until the 1990s. Now parvovirus B19 and Human Herpes Virus 6 are the viruses most frequently found in patients with acute and chronic cardiomyopathy (Figure 1). PCR of endomyacardial biopsies in 624 patients (approximately 60% children) with idiopathic heart failure and biopsy-proven myocarditis showed viral genomes in 38% of cases, whereas viral genomes could only be shown in 20% in myocarditis-negative biopsies of 149 patients with heart failure Bowles. Interestingly, although adenovirus and enterovirus were the most encountered pathogens in both groups, PCR showed other pathogens only in the patients with biopsy-proven myocarditis. Some of these pathogens, especially Parvovirus B19 end Human Herpes Virus-6, were predominantly present in a more recent study, investigating only adult patients (Figure1). There are several potential mechanisms by which a viral myocarditis might cause acute or chronic DCM, including direct viral damage or as a result of humoral or cellular immune responses to persistent viral infection (Figure 2).Our understanding of the pathogenesis of viral myocarditis comes almost entirely from experimental models of acute coxsackie B virus infection. The initial change is myocyte damage in the absence of a cellular immune response. The myocyte injury may be mediated through direct viral toxicity, perforin-mediated cell lysis, and cytokine expression. The second phase which rapidly follows is an innate immune response comprised of altered regulatory T cell function, NK cells, interferon gamma, and nitric oxide. In the third phase, a heart specific immune response is characterized by antibodies to pathogen and host cardiac proteins and autoreactive T cells. Most subjects recover with few consequences, but a minority either die from arrhythmias or progress onto a phase of chronic heart failure. Hemodynamic and neurohumoral stresses lead to ventricular dilatation.

- Giant cell myocarditis

Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis is a rare, virulent, and frequently fatal type of myocarditis that may respond to immunosuppressive therapy. Cooper The pathogenesis of this disorder is not known. In an animal model, a disorder similar to giant cell myocarditis was induced by immunization with cardiac myosin. In this model, myocardial damage is primarily mediated by T lymphocytes.

- Hypersensitivity myocarditis / eosinophilic myocarditis

This is an autoimmune reaction in the heart that is often drug-related and is usually characterized by acute rash, fever, peripheral eosinophilia, and ECG abnormalities such as nonspecific ST segment changes or infarct patterns . However, some patients present with sudden death or rapidly progressive Heart Failure. The true incidence is unknown. One estimate comes from an autopsy study, which identified 16 cases in more than three thousand consecutive autopsies (<0.5 percent). In other series, the prevalence of clinically undetected HSM in explanted hearts ranged from 2.4 to 7 percent. HSM is usually temporally related to a recently initiated medication. Numerous drugs have been implicated (including methyldopa, hydrochlorothiazide, furosemide, ampicillin, tetracycline, azithromycin, aminophylline, phenytoin, benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants). However, myocarditis does not always develop early in the course of drug use. As an example, patients taking the antipsychotic agent clozapine have been reported to develop myocarditis more than two years after the drug was started. Eosinophilic myocarditis has also been seen in 2.4 to 23 percent of patients treated with dobutamine infusion. It is uncertain whether this reaction represents hypersensitivity to the drug itself or a reaction to sodium bisulfite, which is a preservative in many dobutamine preparations. It has been diagnosed either on endomyocardial biopsy or retrospectively after explantation of the native heart. In some cases, tapering or discontinuation of dobutamine infusion has resulted in diminution of the peripheral eosinophilia and histologic improvement. Histologically, HSM is usually characterized by an interstitial infiltrate with prominent eosinophils, but little myocyte necrosis. However, occasional patients with apparent drug hypersensitivity have giant cell myocarditis, granulomatous myocarditis, or necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis. These disorders can usually be distinguished from hypersensitivity myocarditis only by endomyocardial biopsy.

- Celiac disease

It has been suggested that celiac disease, which is often clinically unsuspected, accounts for as many as 5 percent of patients with autoimmune myocarditis or idiopathic DCM. Autoimmune disorders occur with increased frequency in patients with celiac disease and may be related in part to antigen overload resulting from increased intestinal permeability.

- Chagas' disease

This is a protozoan infection due to Trypanosoma cruzi; it is a major public health problem in endemic areas in many South American countries. Morbidity is primarily related to three problems: megaesophagus, megacolon, and cardiac disease. Chagas' myocarditis is by far the most common form of cardiomyopathy in Latin American countries. It is estimated that over 750 thousand years of productive life are lost annually, because of premature deaths due to this disorder. In the acute phase it is characterized by intense and diffuse myocarditis with mononuclear infiltrates. The most characteristic cardiac anatomic lesion in the chronic phase is the ventricular apical aneurysm which, in one series, was noted in 52 % of 1078 autopsied Chagasic patients Oliveira.

- Autoimmune disorders

Systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener's granulomatosis, giant cell arteritis, Kawasaki disease and Takayasu arteritis may cause myocarditis. Among patients with lupus, myocarditis has been found in approximately 9 percent in clinical studies and 6 percent in echocardiography studies in which global hypokinesis is the suggestive finding.

- Lyme disease

Lyme disease is a multisystem disease caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Cardiac involvement occurs during the early disseminated phase of the disease, usually within weeks to a few months after infection. The clinical features of Lyme carditis include heart block related to dysfunction of the conduction system and decreased cardiac contractility due to myopericarditis. Carditis occurs in approximately 5 percent of untreated adults in the United States, particularly among men. Carditis is less frequent in Europe, affecting approximately 0.3 to 4.0 percent of untreated adults. This difference may be related to infection by different organisms. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is responsible for all cases in the United States, whereas B. afzelii and B. garinii are responsible for many cases in Europe, although B. burgdorferi sensu stricto occurs there as well. Lyme myopericarditis is often self-limited and mild, leading to transient cardiomegaly or mild pericardial effusion. In most cases, it is asymptomatic and clinically inapparent. The most frequent manifestation of myocardial involvement in Lyme disease is nonspecific ST and T wave changes on the electrocardiogram . However, occasional patients develop symptomatic myocarditis with cardiac muscle dysfunction and/or associated pericarditis.

- Sarcoidosis

Myocarditis may occur as a complication of other cardiomyopathies including cardiac amyloidosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. In amyloidosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myocarditis may affect prognosis.

Figure 2 : mechanisms for cardiac injury in myocarditis

Clinical features and prognosis of myocarditis

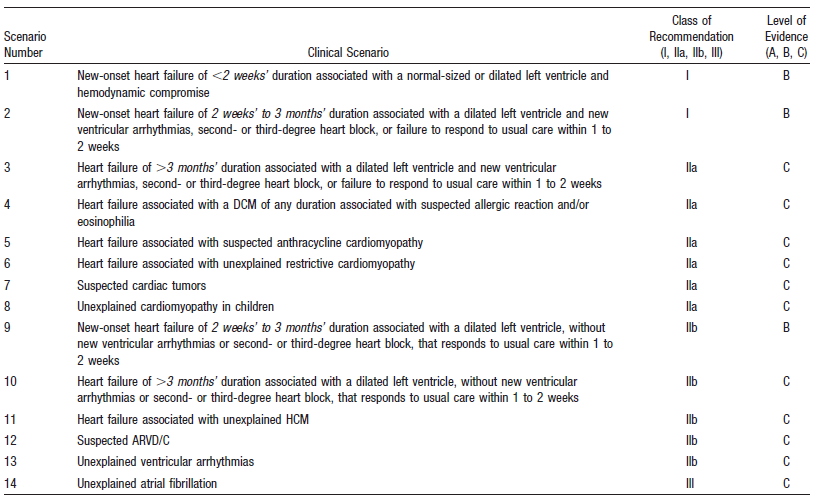

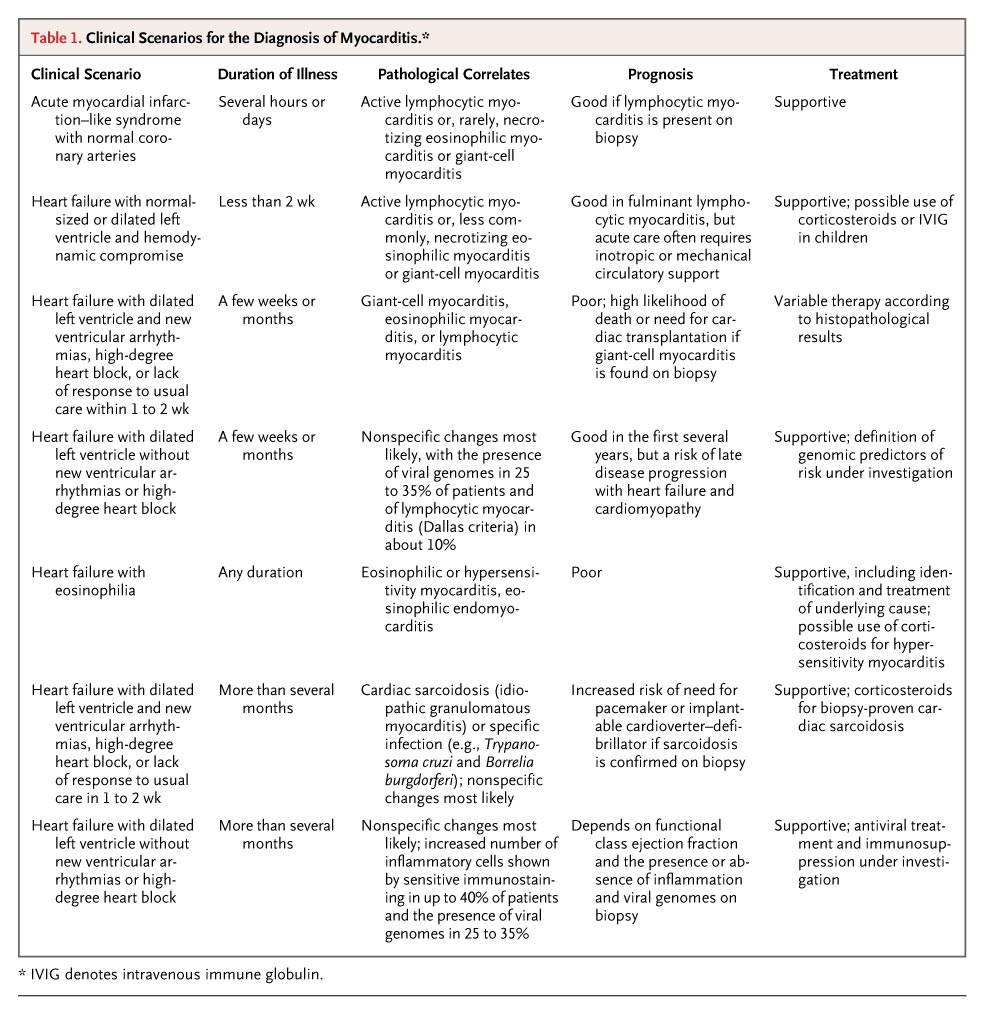

In symptomatic patients, the cardiac presentation is frequently one of acute heart failure , although a syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction or a tachyarrhythmia, including sudden death, or high-grade heart block may occur. If the epicardium is involved, the syndrome of myopericarditis develops, often with pleuritic chest pain and pericardial effusion. Severe illness with systemic manifestations of viral disease and heart failure, often referred to as ‘fulminant myocarditis’, may resolve without symptoms but may also lead to heart failure in a limited number of patients. Prognosis seems relatively good compared to ‘Acute Myocarditis’, presenting with heart failure as the main symptom McCarthy. See Figure 3. Most people with myocarditis who present with acute dilated cardiomyopathy have relatively mild disease that resolves with few short-term sequelae, but certain clinical clues signify those at high risk for more difficulty (Table 2). Rash, fever, peripheral eosinophilia, or a temporal relation with recently initiated medications or the use of multiple medications suggest a possible hypersensitivity myocarditis. Giant-cell myocarditis should be considered in patients with acute dilated cardiomyopathy associated with thymoma, autoimmune disorders, ventricular tachycardia, or high-grade heart block. An unusual cause of myocarditis, such as cardiac sarcoidosis, should be suspected in patients who present with chronic heart failure, dilated cardiomyopathy and new ventricular arrhythmias, or second-degree or third-degree heart block or who do not have a response to standard care. Many symptomatic cases of postviral or lymphocytic myocarditis present with a syndrome of heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy. In patients who develop heart failure, fatigue and decreased exercise capacity are the most common initial manifestations. However, diffuse, severe myocarditis, if rapid in evolution, can result in acute myocardial failure and cardiogenic shock. Signs of right ventricular failure include increased jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly, and peripheral edema. The decline in right ventricular function "protects" the left side of the circulation so that signs of left ventricular failure may not be seen. If, however, there is predominant left ventricular involvement, the patient may present with the symptoms of pulmonary congestion: dyspnea, orthopnea, pulmonary rales, and, in severe cases, acute pulmonary edema. Chest pain is usually associated with concomitant pericarditis. However, myocarditis can mimic myocardial ischemia and/or infarction both clinically and on the electrocardiogram, particularly in younger patients. Myocarditis may present with unexpected sudden death, presumably due to ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. A number of other arrhythmias may be seen. Sinus tachycardia is more frequent than serious atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, while palpitations secondary to premature atrial or, more often, ventricular extrasystoles are common. The electrocardiogram may be normal or abnormal in myocarditis. However, the abnormalities are nonspecific unless there is pericardial involvement. The changes that may be seen include nonspecific ST abnormalities, single atrial or ventricular ectopic beats, complex ventricular arrhythmias (couplets or nonsustained ventricular tachycardia), or, rarely, atrial tachycardia or atrial fibrillation. High grade heart block is uncommon in lymphocytic myocarditis, but common in cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. Myocarditis can, in some patients, exactly simulate the ECG pattern of acute pericarditis or acute MI. Like acute MI, myocarditis may be associated with regional ST elevations and Q waves. Myocarditis should be suspected in young patients who present with a possible MI but have a normal coronary angiogram. The chest radiograph is variable, ranging from normal to cardiomegaly with or without pulmonary vascular congestion and edema. Considerable biventricular cardiomegaly may be associated with the total absence of pulmonary congestion due to the presence of right ventricular failure and/ or moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation. Cardiac enzyme elevations are seen in some but not all patients with myocarditis. Persistent elevations in cardiac enzymes are indicative of ongoing necrosis.

Figure 3 : Survival in fulminant myocarditis vs acute myocarditis

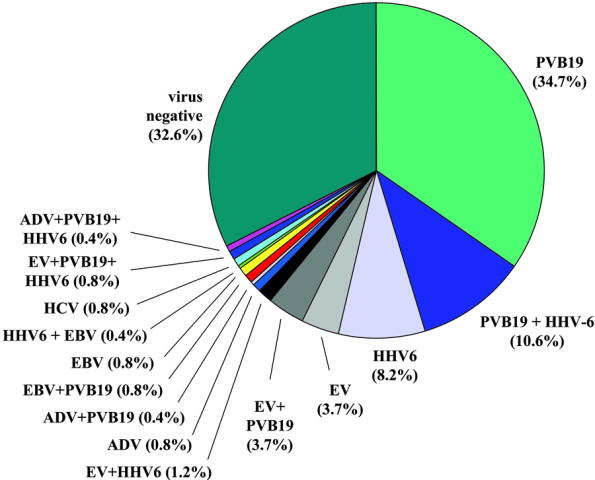

Table 2 : Clinical scenarios Cooper

Diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis

The manifestations of myocarditis described above often suggest the clinical diagnosis. Acute myocarditis should be suspected whenever a patient, especially a young male, presents with otherwise unexplained cardiac abnormalities of new onset, such as heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, or conduction disturbances. A history of recent upper respiratory infection or enteritis may also be elicited in the majority of cases of viral myocarditis. When the patient presents with heart failure and a cardiomyopathy presumed to be due to myocarditis, congenital, valvular, ischemic, and pulmonary heart disease must be excluded. The physician next must consider specific heart muscle disease of noninflammatory nature. There are several other settings in which the diagnosis of myocarditis should be considered:

- When systemic manifestations of a viral, bacterial, rickettsial, fungal or parasitic infection are associated with new abnormalities in cardiovascular function. Since many cardiotropic viruses, including coxsackie A, are also myotropic, the concurrent presence of muscle aching and particularly muscle tenderness in this setting should enhance the suspicion of myocarditis.

- When acute viral infections, especially the exanthematous diseases of childhood due to parvovirus B19, are accompanied by tachycardia out of proportion to fever.

- When an infectious disease presents with evidence of pericarditis.

- When a patient, particularly a young patient, presents with clinical signs and symptoms of an acute myocardial infarction, particularly if the coronary angiogram is normal.

A clinicopathologic classification utilizing both histologic and clinical features may provide prognostic information about patients with heart failure due to myocarditis :

- Fulminant myocarditis — Fulminant myocarditis presents with an acute illness after a distinct viral prodrome. Patients have severe cardiovascular compromise, multiple foci of active myocarditis by histologic study, and ventricular dysfunction that either resolves spontaneously or results in death.

- Acute myocarditis — Acute myocarditis presents with a less distinct onset of illness. Patients present with established ventricular dysfunction and may progress to dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Chronic active myocarditis — Chronic active myocarditis also presents with a less distinct onset of illness. Affected patients often have clinical and histologic relapses and develop ventricular dysfunction associated with chronic inflammatory changes, including giant cells on histologic study.

- Chronic persistent myocarditis — Chronic persistent myocarditis, which also presents with a less distinct onset of illness, is characterized by a persistent histologic infiltrate, often with foci of myocyte necrosis but without ventricular dysfunction, despite other cardiovascular symptoms such as chest pain or palpitation.

The standard Dallas pathological criteria for the definition of myocarditis require that an inflammatory cellular infiltrate with or without associated myocyte necrosis be present on conventionally stained heart-tissue sections. Criteria are limited by variability in interpretation, lack of prognostic value, and low sensitivity, in part due to sampling error. These limitations have led to alternative pathological classifications with criteria that rely on cell-specific immunoperoxidase stains for surface antigens, such as anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD20, anti-CD68, and anti–human leukocyte antigen. Criteria that are based on immunoperoxidase staining have greater sensitivity and may have prognostic value. The lack of consensus regarding the value of invasive studies such as endomyocardial biopsy and the overall good prognosis for patients with mild, acute dilated cardiomyopathy who have suspected myocarditis have led to recent recommendations that endomyocardial biopsy should be considered on the basis of the likelihood of finding specific treatable disorders. Cooper2007. See Table 3. A presumptive diagnosis of myocarditis may be made on the basis of the clinical and laboratory presentations delineated above. This presumption may be strengthened if an echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is characteristic and does not reveal evidence of other forms of heart disease. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging can detect myocardial edema and myocyte injury in myocarditis. Findings include increase in focal and global T2 signal intensity , increase in focal and global early myocardial contrast enhancement relative to skeletal muscle, and presence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) . Late gadolinium enhancement appears to be less sensitive than global relative enhancement or edema ratio for detection of myocarditis, so lack of LGE does not exclude myocarditis. The best diagnostic performance may be obtained by requiring positivity of any two of these three sequences which yielded a 76 percent sensitivity and 96 percent specificity. Abdel-Aty CMR studies have demonstrated that myocarditis often begins as a focal process: In a study using gadolinium-enhanced CMR imaging, 19 patients with clinically suspected myocarditis were compared with 18 normal volunteers. Initial focal increase in relative myocardial enhancement consistent with inflammation became global in serial studies over four weeks. The extent of relative myocardial enhancement correlated with clinical status and left ventricular function. Friedrich In a report of 32 patients with clinically suspected myocarditis, 28 (88 percent) had one or more foci of LGE, most often in the left ventricular free wall. Active myocarditis was found in 19 of 21 patients in whom endomyocardial biopsy was performed in the LGE region and in only one of 11 patients in whom the biopsy was performed outside the LGE region. Thus, use of CMR data to guide endomyocardial biopsy may increase the diagnostic yield. Mahrholdt2004 The pattern of LGE in myocarditis can generally be distinguished from that in ischemic cardiomyopathy. In myocarditis, LGE preferentially involves the epicardium and mid myocardium with sparing of the endocardium. In ischemic cardiomyopathy, LGE reflects the distribution of myocardial infarction which typically involves the endocardium with variable extension into the mid myocardium and epicardium. Different viral pathogens may produce different focal patterns of myocardial injury. Patients with parvovirus B19 (PVB19) have left ventricular lateral wall subepicardial LGE, while patients with human herpes simplex virus 6 (HHV6) and especially HHV6/PVB19 have septal LGE and heart failure. Mahrholdt2006 See Figure 3. These patterns also seem to be predictive for recovery of myocarditis. Prognosis of clinically overt myocarditis is similar to that of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy with a 5-year survival of approximately 56%. Worse prognosis has been associated with syncope, bundle branch block and EF < 40%. Persistence of viral genomes in repeated biopsy seems to be related to worse prognosis. As already mentioned, giant cell myocarditis is a rare and often fatal type of myocarditis. There are a number of causes (primarily infectious) of myocarditis for which there is specific therapy, such as Mycoplasma or Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi). There seems to be a role for antiviral therapy (interferon) in acute and fulminant myocarditis but early results need to be confirmed in larger studies. Kuhl Immunosuppressive therapy by corticosteroids, cyclosporine and azathioprine does not seem to influence prognosis in general and has been shown to exacerbate murine viral myocarditis. Monrad Moreover, the high rate of spontaneous recovery may have clouded the results in human trials. Patients with evidence of chronic inflammation, however, may respond favourably to immunosuppressive therapy. Wojnicz Unlike lymphocytic myocarditis, patients with Giant cell myocarditis treated with certain immunosuppressive regimes may have a significantly improved survival compared to patients who do not receive immunosuppressive treatment . Among 22 patients treated with immunosuppressive medications the average transplant-free survival was 13 months compared with only three months among 30 patients who did not receive therapy. Cooper1997. Myocarditis characterized by a predominantly eosinophilic infiltrate may occur in association with malignancy, parasite infection, hypersensitivity myocarditis (HSM), endomyocardial fibrosis, and with the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. HSM presents as sudden death or rapidly progressive heart failure sometimes with rash, fever and peripheral eosinophilia. Necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis has an exceptionally poor prognosis with most cases diagnosed at autopsy. Eosinophilic myocarditis associated with the hypereosinophilic syndrome typically evolves over weeks to months. The presentation is usually biventricular heart failure, although arrhythmias may lead to sudden death. Treatment usually consists of high dose steroids and removal of the offending drug in the case of HSM or treatment of the underlying disorder. Sarcoid myocarditis may respond to treatment with corticosteroids if given before the development of extensive fibrosis of the LV. It is less clear if steroid therapy prevents conduction disease or ventricular arrhythmias. Some recommend an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) as primary therapy of ventricular tachycardia since there is a high rate of recurrence of ventricular tachycardia with antiarrhythmic drug therapy, even when guided by electrophysiologic testing.

Table 3 : Indications for endomyocardial biopsy

References

<biblio>

- Maron pmid=19221222

- Felker pmid=10760308

- Kuhl pmid=15699250

- Bowles pmid=12906974

- Cooper pmid=19026310

- Oliveira pmid=7295439

- McCarthy pmid=10706898

- Cooper2007 pmid=17959655

- Abdel-Aty pmid=15936612

- Friedrich pmid=9603535

- Mahrholdt2004 pmid=14993139

- Mahrholdt2006 pmid=17015795

- Kuhl2003 pmid=12771005

- Monrad pmid=3698228

- Wojnicz pmid=11435335

- Cooper1997 pmid=9197214

</biblio>